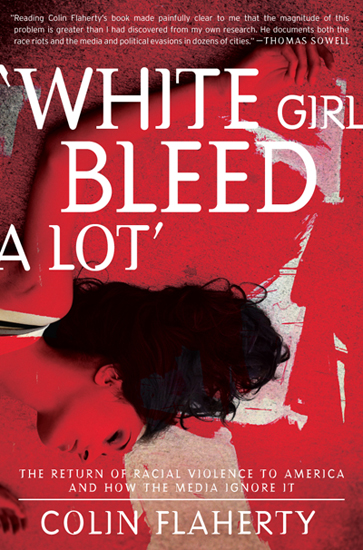

Colin Flaherty, White Girl Bleed A Lot: The Return of Racial Violence to America, Fifth Edition, WND Books, 2013.

In the popular Harry Potter series, arch-nemesis Voldemort is superstitiously referred to as “he-who-must-not-be-named.” He is thought to be so evil, that the mere mention of his name might bring down his wrath or, worse, make him appear.

Colin Flaherty’s White Girl Bleed a Lot: The Return of Racial Violence to America is a reminder that superstitious dread is not confined to the world of make-believe. Mr. Flaherty documents America’s epidemic of black mob violence — and shows that the media ignore it. Mr. Flaherty lists over 500 violent incidents, in over 60 cities, since 2010. The e-book includes links to YouTube videos that capture the violence (the bound volume has still images). The stories are then linked to the media’s sanitized version, and the contrast is jarring. Mob attacks on whites become “fights,” race is never mentioned, and the incidents are buried on back pages, if they are even reported at all.

Mr. Flaherty is an award-winning writer who has been published in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Boston Globe. He has been writing about race since the 1980s, when he was a staffer for Hispanic Republican Uvaldo Martinez, and later as a ghost writer for Clarence Pendleton, the first black chair of the US Civil Rights Commission. He has exposed several fake hate crimes and his reporting for the San Diego weekly, The Reader, led to a black man’s release from prison. He paints a picture of a media-enabled wave of horrific, anti-white violence.

Oh, white girl bleed a lot

The book takes its title from a 2011 Independence Day riot in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The attack started as a flash mob of about 100 “youths” who robbed a BP gas station after a fireworks display. The mob then headed to a nearby park, where 10 to 20 whites were relaxing. Police described what happened next as “fights,” which, Mr. Flaherty says, “is a curious way to describe a riot where some of the victims may have tried to defend themselves.” The thugs ran away when police arrived, and officers refused to file a report or start an investigation.

The next day, victims called police and demanded action. The police chief and mayor held a press conference, but played down the racial angle. As Mr. Flaherty writes:

Over the weekend, the chief said, the city had victims of crime that were black and white and Asian, so that proved ‘crime was colorblind;’ and he did not appreciate that some people on blogs and talk radio were trying to ‘sensationalize’ it.

More victims came forward, however, describing the attacks, the beating, and what the chosen victims all had in common. As public pressure mounted, a local paper finally picked up the story:

Shaina Perry [the victim] remembers the punch to her face, blood streaming from a cut over her eye . . . ‘They just said, “Oh, white girl bleed a lot.” ’

Mr. Flaherty points out that “even a rookie reporter with a scanner would not have missed this type of event. If it was not covered from the outset, it was probably by design.”

It was left to James Harris of 620 WTMJ in Milwaukee to tell the truth:

This was not a colorblind crime. We have this epidemic of black teenage mob violence happening all over the country. It is from a perfect storm of entitlements and white guilt where people are afraid to identify who is doing the crime and why they are doing it. [The mayor and police chief] were more worried about being accused of racial profiling than the fact that black mobs were roaming down the streets hurting people.

The book goes on to describe black mob violence at amusement parks, shopping malls, sports venues, and on public transportation. Most of the attacks were caught on tape, either by surveillance cameras, bystanders, or the perpetrators themselves. And more often than not, the victims they chose were white.

Philadelphia mayor breaks the silence

Philadelphia has seen dozens of rampaging black mobs that loot, assault passersby, and fight with police. As documented by Mr. Flaherty:

February 2010, at a Macy’s department store, a few blocks from city hall, more than a hundred black people erupt in fights and destruction.

In Spring of 2010, police break up a black flash mob in the Tioga-Nicetown section of Philly.

Summer of 2011, Jeremy Schenkel recounted the attack on him to CBS3 Eyewitness News. He says that kids were laughing as they beat him and kicked him, just kind of cheering them on. ‘Almost like an admiring group that was following them, just ragging on people, and one of those guys said, “it’s not our fault you can’t fight.” ’

Emily Guendelsberger and her friends were out for an evening in south Philadelphia during a hot June night in 2011. She had heard about the attacks but wasn’t concerned. As Mr. Flaherty writes, “It was simply cool to pretend to not notice the race of the attackers.” Miss Guendelsberger was an editor for The Onion’s AV Club, a trendy lifestyle guide for “the hopelessly hip.” Mr. Flaherty notes:

Just a year before, Guendelsberger wrote a column for the Philadelphia Daily News about why using the term ‘flash mob’ to describe [the black mobs that were organizing on Twitter] betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding of what was going on.

A mob of over 1,000 blacks descended on the area where Miss Guendelsberger was enjoying the evening, attacked people in restaurants, looted, and caused enormous property damage. A group of blacks herded her and her friends into an alley and beat and robbed them. She spent several days in the hospital with a broken leg.

Miss Guendelsberger insisted there was no racial dynamic. Anyone who thought differently was a “racist” and “creepy.”

Weary of living in denial, black Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter finally took to the pulpit of a black church and admitted his city had a problem with violent young black men. “You have damaged your own race,” he told them. The head of the Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP, J. Whyatt Mondesire, praised Mr. Nutter, saying “These are majority African-American youth and they need to be called on it.”

And Miss Guendelsberger? Two months after the attack, fortified by the mayor’s admission, she told NPR:

I’m afraid of young black men now. It’s very annoying because there are a lot of young black men in Philadelphia. I honestly just wish I could go back to how I was before.

Dancing on our graves

One medium that hasn’t missed the social importance of being able to attack with impunity is rap videos. Mr. Flaherty includes a chapter on the videos that are being created either with actual riot footage or encouraging lawless behavior. Philadelphia has a starring role simply because of the sheer number of attacks that have occurred there. Other videos run the gamut from grainy, novice clips to sophisticated, highly-polished productions that urge blacks to do everything “from murdering CEOs and delivery drivers to starting riots and engaging in guerilla warfare.”

Dr. Dre’s ode to the L.A. riots, “The Day the Niggaz Took Over,” set the tone for what a riot is truly supposed to be about: “Break the white man off something lovely / I don’t love them so they can’t love me.”

Ded Prez brags “White boy in the wrong place at the right time / Soon as the car door open he be mine / We pull up quick and point the pistol to his nose / By the look on his face he probably shit his clothes.”

“Riot,” a 2 Chainz video, has had over 3 million viewers. In it, the rapper promises “And if you fuck with us we gon’ start a riot / I’mma start a riot, I’mma start a riot.”

Stockholmed media

Mr. Flaherty writes that he was inspired to write this book after noticing a pattern of violence across the country, and a curious lack of media coverage or public acknowledgement. The riots–some would even call them race war–all had the same features, but when he showed the YouTube footage to other journalists, they would deny the incidents were riots. Even when all the assailants were black and the victims were white; even when the rioters yelled racial slurs; even when it involved large-scale public disturbances; and even when the rioters themselves said they were in a race riot, journalists were stuck in a Stockholm-like trance of denial.

Mr. Flaherty includes chapters on black mob violence against homosexuals and Asians to round things out and perhaps to fend off charges of “racism.” But the attacks against whites are the most highly charged and menacing. Mr. Flaherty draws no conclusions and proposes no solutions — although he mentions a few armed citizens who defended themselves against mob violence. He simply recites events and takes the media to task for failing in its reportorial duty.

- Post TagsBlack on White Crime, Book Review, Censorship, Classics, Crime, Media Bias, Murder, Philadelphia, Racial Conflict