The Rise and Decline of Anglo-Australia

- Post AuthorBy Thomas Jackson

- Post DateThu Jan 26 2023

Alan James, New Britannia: The Rise and Decline of Anglo-Australia, Renewal Publications, 2013, 217 pp.

Australia, like the United States, was founded by the British. Both countries were built by white settlers and populated by white immigrants. Both had immigration policies strongly favoring white immigration that continued until just a few decades ago. But Australia had even more racially explicit origins than the United States. It came into being as a nation dedicated not merely to racial purity but to preserving a specific ethnic heritage. The “White Australia Policy” was really a “British Australia Policy,” established by a people who, as Prime Minister Robert Menzies said, felt “British to the bootstraps.” What happened to this proud, fiercely explicit identity?

In New Britannia, independent scholar Alan James traces what he calls “the rise and decline of Anglo-Australia.” It is a story of betrayal that almost perfectly parallels that of the United States. Beginning as early as the 1930s, intellectuals, bureaucrats, and politicians deliberately flouted the desires of the vast majority of Australians and opened the country to immigrants utterly unlike the founding stock.

The penal colony

Until the American Revolution, the North American colonies were a handy dumping ground for British convicts. The newly independent United States refused to accept prisoners, however, so that is why, beginning in 1787, Britain shipped convicts to Australia. The plan was also for them to be the founding population of a British colony to counter France in the South Pacific. The first governor, Arthur Phillip, accordingly set the pattern: Once an exile had served his term he was to be treated as if his record had been wiped clean.

Britain continued to send convicts to Australia until 1868, by which time a total of 132,000 men and 25,000 women had been transported. Today’s Australians like to point out that the convicts were not degenerates–most were petty thieves; more serious criminals got the death penalty. The average age on arrival was 27, and convicts were chosen in part because they were healthy and would make good settlers. Even from the earliest days, there was a handful of volunteer settlers, and by the 1820s, one fifth of all arrivals were free immigrants.

Britain encouraged free emigration, and in 1832 started helping pay passage to Australia. Because most of the convicts and many of the emigrants had been men, there was great demand for women, and more women than men took subsidized passage. The sex ratio evened out only in 1880.

That century-long imbalance gave rise to what Australians call “mateship,” or male camaraderie. Men did not have women and had to depend on other men. At the time of a constitutional referendum in 1999, then-Prime Minister John Howard even tried to put a reference to “mateship” into the preamble to the constitution.

Mr. James notes that Australian colonists considered themselves loyal Britons. He writes that the only exceptions were Irish Catholic political dissenters who were sent down after the failed revolt of 1798. They nursed their hostilities and staged the only insurrection in Australian history. In 1804, about 300 escaped convicts stole weapons and demanded a ship to sail to Ireland. About 15 were killed in what is called the Battle of Vinegar Hill, and nine ringleaders were executed. Mr. James writes that this soured English-Irish relations in Australia for some time, but that for the most part, Scots and Irish assimilated to British patriotism.

White Australia

The first rejection of non-white immigration goes back to the 1830s. By then, landowners had large holdings and wanted cheap labor. They petitioned to bring in Chinese coolies, but both the colonial and British governments refused to consider admitting people of “an inferior and servile description.”

It was the gold rushes, starting in 1851, that brought the first non-whites. Chinese began coming in 1854, and by 1858 there were 40,000 in the gold fields of Victoria. White miners disliked their alien habits and complained that when Chinese were successful they sent their earnings back to China. The colonial governments of the time tried to curb Chinese immigration by taxing new arrivals and limiting the number who could arrive on a single ship, but gold was too strong a lure.

Tensions peaked in 1857, when 700 white miners attacked a camp of 2,000 Chinese. In what is known as the riot of Buckland River, they looted the camp, burned down a temple, and killed a handful of Chinese. Other Chinese drowned in the river trying to escape. It took the police three days to get out to the campsite and restore order. Thirteen white rioters were arrested, but juries refused to convict nine of them, and the remaining four got only nine months of prison.

In 1860, whites in the colony of New South Wales killed two more Chinese miners, and insisted on complete exclusion. They also set new words to the popular patriotic song, “Rule Britannia:”

Rule Britannia:

Britannia rules the waves.

No more Chinamen allowed

In New South Wales.

The colonial government found itself spending so much money protecting Chinese miners that it finally gave in and restricted Chinese immigration in 1861. In 1888 it passed a bill completely excluding Chinese.

In 1901, what had been separate British colonies united to form the Commonwealth of Australia, and its citizens wanted the commonwealth to stay white. As the first prime minister Edmund Barton explained, “We are guarding the last part of the world in which the higher races can live and increase freely for the higher civilization.” The second prime minister, Alfred Deakin, was even more explicit: “Unity of race is absolutely essential to the unity of Australia. It is more, actually more in the last resort, than any other unity . . . .”

Mr. James points out that this was the overwhelming view. In its very first year, the commonwealth passed a law to exclude all non-whites. Britain maintained veto power over some legislation, however, and could have overruled explicitly racial legislation. Australia therefore adopted the method pioneered by the South African colony of Natal and known as “the Natal formula.” This required prospective immigrants to take a dictation test in a European language. It could be any European language, so an English-speaking Indian could be given a dictation test in Italian, which he would certainly fail.

Labour was the only party that opposed this law; it insisted on an undisguised racial ban. As was the case in the United States at the period, spokesmen for working people were open advocates for whites. When a commonwealth-wide Labour Party was established in 1900, the number-two plank in its platform was “Total exclusion of coloured and other undesirable races.” For Australians, non-white immigration was unthinkable.

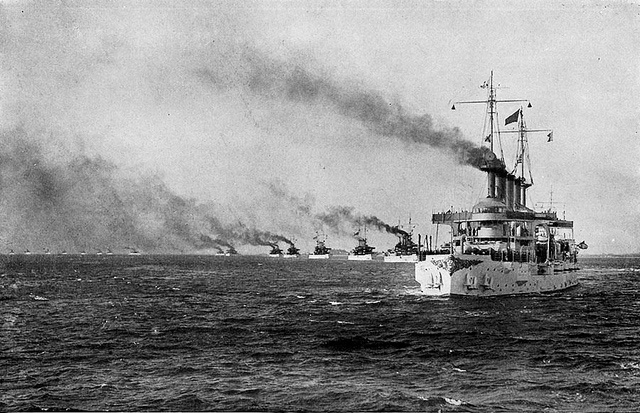

In 1907, Teddy Roosevelt sent “The Great White Fleet” on a round-the-world voyage to show the American flag. Australia welcomed the ships in the spirit of racial and even British solidarity. As Sydney author Joe Slater put it:

When they reach our sunny land we’ll extend a friendly hand,

And we’ll treat them all as brothers taut and true,

For when all is said and done, as a race we all are one,

All descended from the old Red, White, and Blue.

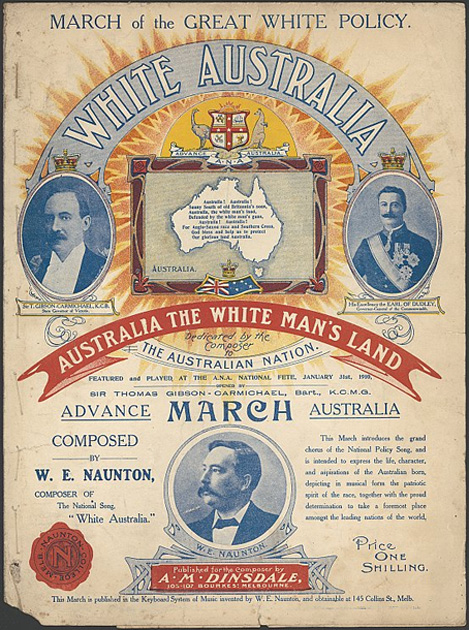

“Australia, the White Man’s Land,” was a piece of music published and first performed in 1910. It included such words as:

Sunny south of Old Britannia’s sons,

Australia the white man’s land,

defended by the white man’s guns.

God bless and help us to protect our glorious land Australia.

In 1919, Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes attended the Paris Peace Conference. During the negotiations to draft the covenant of the League of Nations, Japanese proposed a declaration of racial equality. Hughes successfully led the opposition to what he saw as an assault on the White Australian Policy.

Ordinary Australians continued to take race for granted, but a few “intellectuals” were beginning to low-rate their own country. Mr. James quotes a 1939 poem by Alec Derwent Hope (1907–2000):

Without songs, architecture, history . . .

And her five cities, like five teeming sores

Each drains her: a vast parasite robber-state

Where second-hand Europeans pullulate

Timidly on the edge of alien shores.

This was a considerable change from poetry of an earlier time. Mr. James also quotes Mary Gilmore’s (1865-1962) Old Botany Bay, which celebrates the convict pioneers:

I am he

Who paved the way,

That you might walk

At your ease today;

I split the rock;

I felled the tree,

The nation was —

Because of me!

Mr. James writes that the first official breaches in the White Australia Policy occurred after the Second World War. There had been a number of non-white refugees from Japanese aggression who had been allowed temporary residence during the war, and most went home — as they had promised — when peace came. Some insisted on staying, however, and there was a raucous debate over whether they should be forcibly deported. In the end, some 800 were allowed to stay — a clear and ominous deviation from long-standing policy.

During the allied occupation of Japan, a number of Australian soldiers married Japanese women. The wives were let in — another deviation from policy, but one justified on the grounds that there were very few war brides. Prime Minister Robert Menzies assured the public that these exceptions did not mean a change in policy.

By the 1950s, however, for the first time, there were organized groups calling for non-white immigration. Mr. James notes that members were Communists and church leaders — with a high proportion of Irish Catholics. In 1959, something called the Immigration Reform Group, set up mostly by academics, called for an end to the White Australia Policy.

In 1961 came what Mr. James considers a very significant event: A man named Peter Heydon became head of the Department of Immigration. Mr. James does not explain what led to this appointment, but Heydon’s view was opposed to that of the government of the time, and he set about filling the department with people who wanted non-white immigration. Heydon was followed by Billy Snedden, who also favored non-white immigration. There had been no official change in policy, and no cabinet member would have called for such a change. This appears to have been a purely bureaucratic, almost undercover takeover of a crucial department.

Changes were working their way through Australian society. Ominously, in 1965, the Labor Party (it switched from “Labour” in 1912) dropped any reference to “white Australia” from its platform. This was open betrayal of the principle labor had stood for ever since the mid-19th century. Perhaps coincidentally, 1965 was the same year the United States abolished its national-origins immigration quotas.

In 1971, then-Prime Minister John Gorton explained his reasons for the switch in policy:

I think if we build up gradually inside Australia a proportion of people without white skins, then as that is gradually done, there will be a complete lack of consciousness of differences between the races. And if this can be done as I think it can, then that may provide the world with the first truly multi-racial society with no tension of any kind possible between any of the races within it. At any rate, this is our ideal.

Australia obviously had no obligation to undertake an experiment of this kind, and Gorton himself acknowledged that success was not guaranteed. This wooly thinking prevailed everywhere in the West.

By 1972, the White Australia Policy was officially dead, and by the 1980s Asian immigration was in full swing. Labor governments especially promoted it, and the unions — always closely aligned with Labor — said nothing. This was a typical stab in the back. A party that was firmly on the left in terms of supporting labor’s demands on capital was captured by leftist silliness on race — and probably many other things — that had nothing to do with working-class interests. The media fell into line without a hiccough.

Mr. James notes that by the time of the “Blainey Affair” in 1984, there was a hard consensus against the traditional policy. Geoffrey Blainey, one of Australia’s most eminent historians, wrote cautiously about the ethnic tensions that can arise in mixed-race societies and suggested that levels of Asian immigration were too high. He was mercilessly hounded, called all the usual names, and was visibly shattered by the attacks. As Mr. James points out, this kind of public flogging has a chilling effect on anyone else who is tempted to step out of line.

By 1991, when a report appeared on the actual costs of accommodating foreigners and non-English-speakers, it was common to say that costs do not matter at all, that civilization itself requires the repudiation of “racist” policies.

Mr. James notes that all the pillars of Australian society — media, churches, politicians, academics — conspired to flout the will of the majority. He quotes tellingly from an admission by former prime minister Robert Hawke:

[T]the major parties had reached an implicit pact to keep immigration off the political agenda. . . . [T]here are no other issues to which the major parties have been prepared to act in this way . . . to advance the national interest ahead of where they believed the electorate to be.

Journalist Gwynne Dyer approved of deception in the name of “ethnic diversification.” He said the government was right to “do good by stealth:” “Let the magic do its work, but don’t talk about it in front of the children. They’ll just get cross and spoil it all.”

This is typical of the contempt in which elites hold the people. Displacing the founding stock with aliens is wonderful, but somehow its wonders are not easily grasped by the people being displaced. Therefore, let the policy be carried out in secret.

The assault on Anglo-Australia

Mr. James is proud of his British heritage, just like the Australian majority. He sees “ethnic diversification” as an open assault not just on white Australia but British Australia.

Unlike the United States, Australia did not have to fight for independence and for generations maintained ties to Britain that verged on veneration. When the British general, Charles “Chinese” Gordon was killed in Khartoum in 1885, a British expeditionary force was formed to avenge him. No fewer than 770 volunteers sailed from Sydney to join it, and two-thirds of the city’s population is said to have seen them off. Sixteen thousand Australian volunteers fought for the British in the Boer War and other wars in Southern Africa. Australian volunteers wanted to help put down the Boxer Rebellion but arrived too late to take part. An astonishing 60,000 men — all volunteers — died for Britain in the First World War. Mr. James sees these sacrifices as entirely natural for men who believed they were fighting for their kinfolk and for the empire.

Robert Menzies — “British to the bootstraps” — visited Britain for the first time in 1935. He wrote touchingly of what “move[s] the soul of those who go ‘home’ to a land they have never seen . . . .”

The 1930s saw a lull in immigration by Britons, who were outnumbered by continental Europeans. Europeans were white, but they were not British, and in 1936 Australia resumed subsidized passage from Britain. A few barriers were also set up to non-British European immigration. Mr. James notes that in 1939, Europeans were required to submit photographs with their visa applications. One purpose was to weed people who looked Jewish, on the assumption that anti-Semitism would never take root in Australia if there were no Jews.

The Second World War was an important turning point in relations with Britain. Australia was shocked by the British surrender of Singapore, which put 16,000 Australian prisoners into the hands of the Japanese. Churchill also insisted on sending Australian troops to Europe rather than let them stay to fight Japan. Instead of serving under British command as they always had, Australians fought under American officers. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation, which had always played “The British Grenadiers” before new broadcasts, switched to “Advance, Australia Fair” in 1942.

Old ties were not easily broken, however, and free and assisted passage from Britain continued after the war. From 1947 to 1973, more than one million new British settlers arrived to the slogan of “Bring out a Brit.” The British stopped subsidizing fares in 1972, but the Australians kept paying until 1981. When Australian citizenship was introduced in 1948, British immigrants could apply after only one year of residence, as opposed to longer periods for others. British immigrants also had preferential admission into the military.

Mr. James looks back with nostalgia on Anglo-Australia. He notes that until the 1970s, school children in the state of Victoria saluted the Australian flag every day, and listened to “God Save the Queen.” Until the 1960s, cinema played “God Save the Queen” before the movie — and everyone rose. The queen’s portrait was in government buildings, scouting halls, schools, and council chambers, but these began to disappear in the 1970s.

Some shifts were voluntary. A 1977, referendum changed the national anthem to “Advance, Australia Fair.” However, despite near-monolithic media support for a republic, voters — most recently in 1999 — choose to remain subjects of the Queen.

“The Founding of Australia. By Capt. Arthur Phillip R.N. Sydney Cove, Jan. 26th 1788” painted by Algernon Talmage in 1937.

Still, Mr. James notes that on the Left, the switch to a multi-culti Australia has been accompanied by rituals of contempt for Britain. The uncomplimentary Australian word for the Brits is “poms,” as in “whingeing [whining] poms” and “pommy bastards.” Despite the typically lefty prohibition against “negative stereotypes,” the British, and white Australians by extension, are the only people one may savage with impunity. Mr. James cites a headline to a story about litter left on a tourist beach: “Filthy Poms.” He notes that there are plenty of other tourists on the beach, but would a newspaper dare write about “Filthy Japs”?

Insulting the British is a way to spit on the White Australia Policy. If anyone shows nostalgia for pre-multi-culti Australia, it is fashionable to retort that in those “meat and three veg” days Australians didn’t even know how to eat, and that turning their backs on Britain was the best thing Australia ever did.

Why did it happen?

Mr. James has given us an eminently readable account of a once-sturdy people running itself onto the rocks. What it lacks, though, is what most such accounts lack: a convincing explanation for why Anglo-Australia conceived a hatred for itself and decided to ring its own death knell.

This is not entirely Mr. James’s fault. The multiculturalists have often acted in secret, and conniving media never demand an explanation that goes beyond slogans about diversity and silly jabber about ethnic food. Every nation of the British diaspora has the same miserable record: Canada, the United States, and New Zealand all forsook their roots. None consulted its people or explained why the founding stock was suddenly not good enough.

It is sad to read such convincing confirmation that our own disease so badly infects our Australian cousins, but it is gratifying to know that a few are still healthy, and are determined to save their country.