Eric Zemmour, Le Suicide Français, Editions Albin Michel, 2014, 527 pp. (softcover only, in French).

Eric Zemmour is a well-known French author and television personality. Of Algerian-Jewish origin, he may seem an unlikely spokesman for French tradition, but he has emerged in recent years as a prominent scourge of ideological orthodoxy. He is unquestionably the most prominent mainstream French commentator who speaks candidly about race.

This role comes with a price. In 2011 he was convicted of “incitement to racial hatred” for pointing out that most drug dealers in France are blacks and Arabs. He was again convicted of the same offense for maintaining that employers should be able to hire as they see fit (i.e., to “discriminate”). This year, he has been prosecuted for remarks about the criminal behavior of ethnic gangs.

His latest book, The Suicide of France, was released on October 1st and immediately became the top seller in France, displacing a tell-all memoir by President François Hollande’s former mistress. The book is a year-by-year chronicle of France’s dissolution — everything from harmful legislation to pop songs and movies that reflect or promote decline.

Eric Zemmour in 2012. (Credit Image: Thesupermat via Wikipedia)

One of Mr. Zemmour’s principle themes is the role of free markets in promoting a present-oriented consumerist mentality that has squandered France’s moral capital. However, he also laments the loss of will by native Frenchmen and their displacement by mostly-Muslim immigrants. He has clearly struck a chord among those who are angry at the psychological capitulation of the past 40 years.

The beginning of the end

Mr. Zemmour argues that four quite different developments in the 1970-1972 period set the stage for ongoing France’s suicide. The first was a 1970 law that abolished paternal authority within the family in favor of “parental authority” shared between spouses. Fathers, in Mr. Zemmour’s words:

incarnate the law and the reality principle as against the pleasure principle. They channel and curb children’s impulses in order to sublimate them. [But] fathers are an artificial, cultural creation who need society’s support to overcome natural maternal power.

In 1970, they lost that support. Mr. Zemour also believes that giving the mother equal power in the household pushed France decisively away from saving and towards consumption.

The second crucial development was a 1971 decision by the Constitutional Council, which has the power to declare laws unconstitutional. This was a complex case, but was the first time the Council went beyond checking laws for conformity with a higher legal norm and censured a law politically because of its content. Thus did France, in Mr. Zemmour’s words, “unknowingly abandon the shores of the Republic and enter with eyes closed upon the bumpy road of government by judges.” Americans are all too familiar with judges who seize legislative authority.

The third blow came in 1971 when President Nixon abolished the gold standard. This effectively nullified the Bretton Woods Agreement to which France was a signatory, and ushered in our current era of free-floating fiat currencies. Freed from the constraints of the gold standard, governments no longer worry about deficits. France has not had a balanced budget since 1981.

The fourth and final blow of this period was the so-called Pleven Law of 1972 (Socialists pushed it, but it is named after the Gaullist minister who adopted it), prohibiting “provocation to discrimination, hatred or violence” against persons or groups “on the grounds of their origin or their membership or non-membership in a particular ethnic group, nation, race or religion.” Passed unanimously amid much self-congratulation, this law, in Mr. Zemmour’s words, “introduces subjectivity where objectivity had prevailed; it condemns intentions and not acts; it gives judges the right and the duty to probe into people’s hearts and souls, to dig up thoughts and ulterior motives.”

The author emphasizes the significance of including “nation” among the protected categories. President Georges Pompidou was at that time bringing literally millions of foreign workers into France at the behest of the construction and automobile industries, and the Pleven law meant that no one could criticize their presence.

As Mr. Zemmour points out, the very concept of a nation requires discrimination — a determination that some people are “us,” while the rest are “not us.” Taken literally, a prohibition against making this distinction is incompatible with the continued existence of France, and in practice, the law is used to silence criticism of demographic displacement. As Mr. Zemmour has discovered, even citing verifiable facts can lead to a conviction.

The government made matters much worse by subcontracting the authority to prosecute under the Pleven law to private “anti-racist” organizations such as LICRA (French acronym of the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism) and MRAP (Movement Against Racism and for the Friendship between Peoples). “By authorizing them to take legal action against any unguarded opinion,” notes the author, “the State has given them the right of political and financial life or death over all dissidents.” Americans can imagine the consequences of giving the Southern Poverty Law Center the power to prosecute someone for any remark it did not like.

The Pleven law has been followed by other laws in the same spirit: the Gayssot law of 1990 against “Holocaust denial,” the Taubira law of 2001 defining the African slave trade as a “crime against humanity” and the Lellouche law of 2002 stiffening the penalties for “racist and anti-Semitic offenses.” As Mr. Zemmour notes:

Beginning with the Pleven Law, a whole new field of sacred objects has arisen: immigration, Islam, homosexuality, the history of slavery, colonialism and the Second World War, the Nazi genocide of the Jews. A vast and varied domain that continues to grow, in order to satisfy all the minorities that consider themselves discriminated against.

For future historians, notes Mr. Zemmour, “freedom to think, write and express oneself will have been no more than a historical parenthesis of less than a century.”

Demographic displacement

One year after the Pleven law was passed, the oil crisis of 1973 dried up the demand for foreign workers:

Logic would have dictated that a reverse flow be initiated. This is how the republic had acted during each economic crisis in order to protect “national” employment. Nothing was done by either right or left. This was the first essential break with the past, supposedly for humanitarian reasons.

And the French government went further, passing a “family reunification” law to bring the wives and children of North African workers to France. The result was that “hundreds of thousands of women and children were pulled up from their villages and their modest but peaceful lives to rejoin husbands and fathers they hardly knew.” Housing construction could not keep up, and shantytowns began to appear. Schools were overwhelmed and the quality of instruction for native French children sank as overworked teachers tried to teach Arabs to use toothbrushes and not to slaughter sheep in bathtubs.

In 1959, De Gaulle had warned his countrymen: “The French are French. The Arabs are Arabs. Those who believe in integration have the brains of hummingbirds.” Some politicians still understood this. In 1976, Prime Minister Raymond Barre tried to abolish family reunification, but was overruled by the State Council, which acts as the supreme court for administrative decisions. He then offered “return aid” of 10,000 francs to immigrants who agreed to go home. Spanish and Portuguese who were causing no problems took up the offer, while the North Africans at whom it was aimed stayed put. Barre then negotiated an agreement with the Algerian government for the repatriation of Algerians. Before its terms could be carried out, the Socialist François Mitterand was elected president and repudiated the agreement.

Pop culture as sign of the times

Popular culture quickly took up the immigrants’ cause. The movie Dupont-Lajoie (1975; English title The Common Man) featured hard-working Algerians consigned to ramshackle barracks as they build vacation homes for rich Frenchmen. Vacationers bully the workmen, suspecting them of having intentions on their daughters. A fight breaks out between the two groups, and the police arrest only the Algerians. Later, one particularly “racist” Frenchman murders a woman and tries to blame the Algerian workmen by depositing her corpse near their barracks. The movie’s final scene shows one of the Algerians tracking down the principle French “racist” at a Paris bar and shooting him dead in righteous revenge.

The music business took up the cause of “anti-racism” with Lily, a song about a Somali girl who comes to France to empty trashcans. She is tormented by racists. She is turned away from a hotel in the rue Secrétan that “only accepts whites.” She falls in love with a French boy, but the family objects. She moves to America where she meets the great Angela Davis, but learns that blacks are not allowed to ride on buses. She marries and has a baby “the color of love.”

Lily was issued as a B-side, but French disc jockeys made it a hit. Mr. Zemmour reports that journalists actually hurried to the rue Secrétan in search of the hotelier who turned away blacks; he was, of course, as fictional as the American buses restricted to whites. The lyrics of Lily are now “studied” as literature in French classrooms; questions about the song are sometimes even included in final exams at French secondary schools.

The hunt for fascists

On October 3, 1980, a bomb exploded outside a synagogue in the rue Copernic in Paris. The explosion had been timed to kill worshipers as they left the building, but the service ran late that day. Four bystanders were killed instead.

The attack was carried out by an Arab holding a forged Cypriot passport. He was sponsored by East European communists and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine — but it took years to establish this.

In the meantime, the entire French left was convinced that the attack could only have been the work of the native French “extreme right.” A tiny group called the Federation for National and European Action actually claimed responsibility; only much later was it discovered that the message had come from an infiltrator. The police went in search of Spanish Francoists, but that trail lead nowhere. Jewish youth demonstrated in the streets and sacked the offices of one nationalist organization. Mr. Zemmour explains their mindset:

Since the Six Day War of June 1967, a fraction of French Jewish youth had enrolled in Zionist defense movements. They struck out against imaginary Nazis in the streets and universities … pretending they were in the underground with Jean Moulin [the famous Resistance fighter] or in the Warsaw ghetto.

Shots were fired at the Paris headquarters of Oeuvre Française, another nationalist organization. Right-wing think-tanks such as GRECE and the Club d’Horloge were denounced for “contributing to the atmosphere” in which such a crime could take place. Socialists screamed that the Gaullist President Giscard d’Estaing was an “accomplice of the murderers.” Prime Minster Raymond Barre’s statement that “this odious attack was aimed at Jews attending synagogue, but struck four innocent Frenchmen who were crossing the rue Copernic” was unaccountably held up as proof he was an anti-Semite.

The hue and cry may have contributed to Socialist President François Mitterand’s victory the following year. The truth came out only after the collapse of communism and the opening of the East German secret police files.

The bombing in the rue Copernic provided the standard script for responding to any future anti-Jewish attacks by Arabs:

More than thirty years later, during the presidential campaign of 2012, [three] Jewish children were murdered in front of a religious school. Everyone denounced the fascist-racist-anti-Semite … The media looked for a tall, blond Nazi with a Kalashnikov.

The killer was soon discovered to be an Arab with French citizenship but Mr. Zemmour notes that without missing a beat, the French media then started assuring the country that the crime in no way implicated the Muslims of France or their peaceful religion.

Immigrant insurrection

Unrest in immigrant neighborhoods began in a small way during the 1970s, but the election of François Mitterand, a Socialist, emboldened rioters. Certain they would not be sent home, young North Africans in the Minguettes neighborhood south of Lyon threw a Molotov cocktail at the automobile of the last policeman who lived in the area, shouting “no more cops in the neighborhood!” The officer moved out. This was the first widely reported example of the torching of automobiles, which became a standard form of immigrant “protest.” The government responded by creating recreation programs to serve the “youth.” The lesson was not lost on them: Violence was rewarded.

Following further riots in 1990, Mitterand established a formal Ministry for Urban Affairs in an attempt to buy social peace. Much money was also spent tearing down old buildings in immigrant neighborhoods and erecting new ones, or moving immigrants around from place to place. The very ineffectiveness of these policies was not the least of their attractions to France’s bureaucrats, since it meant disbursements would never end.

Young immigrants have made a New Year’s Eve tradition out of torching cars, though the total for every December 31 has come down to just over 1,000.

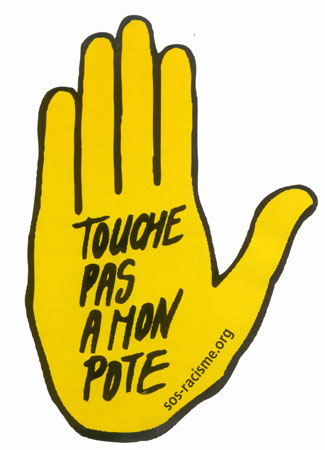

SOS Racism

The anti-racist firmament of France received a new star in October 1984 with the establishment of SOS Racism.

It was at the Elysée Palace [residence of the French President] in great secrecy that the association was formed. Political advisors and presidential spokesmen were involved, and Mitterand was at the helm. The misadventure of a young Black man, Diego, accused of theft in a subway train, was invented out of whole cloth and broadcast by all the media.

SOS Racism went from triumph to triumph, attracting the endorsement of many popular entertainers and repeatedly stressing the alleged historical continuity between French distaste for African immigration and the Nazi persecution of the Jews. SOS Racism at one time hoped to displace older anti-racist groups such as LICRA and MRAP, but Mr. Zemmour believes that Arab suspicion of its heavily-Jewish leadership kept it from ever getting popular support.

Without ground troops or any hold on the ‘street,’ the directors of SOS Racism fell back on their core activity, collecting [state] subsidies. They developed a form of media activism, using their incomparable Trotskyist savoir-faire to manipulate minds, becoming inquisitors of the anti-racist religion, preaching and catechizing on television, performing excommunications, privatizing the justice system for their own benefit like latter-day Torquemadas.

The directors of SOS Racism have a well-earned reputation for living well, dining in the best Paris restaurants, and sporting high-priced designer watches and briefcases. Since most of their money comes from subsidies, the authorities have looked into some of this behavior, but so far there have been no convictions.

The veil

As ongoing demographic displacement of the native French became a taboo subject in the media, a comparatively trivial side issue occupied the headlines.

On September 18, 1989, three teenage girls were sent home from school for refusing to take off their Islamic veils in class. The case made international headlines, and 1,000 people demonstrated in Paris in support of the girls. The government avoided making any decision: The Minister of Education asked the Constitutional Council for a ruling, but this august body left the matter to the discretion of school teachers. The debate raged for 15 years.

In 2004, President Jacques Chirac finally summoned the nerve to ban the veil in French classrooms. But a lot had happened in the meantime.

As the Republic laboriously won the battle of the veil, it failed to notice that it had lost the battle of halal [ritual Muslim slaughter]. In neighborhoods where the Muslim population was becoming the majority, it imposed its cultural and religious dominion. The multiplication of halal butcher shops was the symptom of an Islamization from below which went far beyond mere culinary habits to affect every domain of existence: dress, language, sex, marriage, education, family …

The Republic had no sooner succeeded at great cost in limiting the fire at one spot when it immediately caught on in another. The veil, prohibited at school, was worn at work, in nursery schools; veiled mothers came to pick up their daughters at school; they demanded more or less violently that their children be served halal meat in the cafeteria, sometimes going so far as to demand tables separate from the “infidels;” pupils refused to learn certain subjects: Darwinism that rejects the sacred teaching of the Koran, the history of the Crusades, the unbelieving Voltaire, the unfaithful wife Mme Bovary, the Holocaust of the Jews who are murderers of Palestinians, etc. Girls could not take gym class; boys dropped out en masse; the rare good students were mocked as ‘Jews’ or ‘dirty Frenchmen.’

All of this happens with the blessing of the French left, which continues to imagine that Muslim immigrants will one day give up Islam to join them in worshiping the goddess Reason.

The “undocumented”

In June 1996, 300 illegal immigrants — mostly black Africans — occupied the Church of Saint Bernard in Paris to demand “regularization.” In their eyes, they were not at fault for entering France illegally; it was France that was at fault for not giving them permission. They set up sleeping pallets, urinated and defecated inside the church, and created a great deal of disorder.

French movie starlets and highly-placed administrators showed up to be photographed lending support to the protest — but preferred to go home at night to their own homes. Mr. Zemmour notes that for the crowds supporting them, the Africans variously represented latter-day Jews being persecuted by French successors to the Nazis, formerly colonized persons to whom reparations were due, persecuted Christ figures, noble savages innocent of the moral and ecological contamination for which civilization is responsible, or exploited proletarians who had become agents of revolution. For the captains of industry, meanwhile, they represented low-wage replacements for French workers.

Eight weeks later, on August 23, the security police cleared out the church and shipped at least some of the Africans home. They became martyrs and the anniversary of the raid has been commemorated by French “anti-racists” ever since.

Le Pen makes the second round

Between 1997 and 2002, France was governed by Gaullist (conservative) President Jacques Chirac, but parliamentary elections had resulted in a left-leaning legislature with a Socialist Prime Minister, Lionel Jospin. This arrangement, which the French call “cohabitation,” pleased nobody. In the Presidential election of 2002, president and prime minster ran against each another. Neither man was popular. President Chirac, embroiled in a financial scandal, received less than twenty percent of the vote — a humiliation for an incumbent. His prime minster, opposed by half a dozen other leftist parties, picked up just sixteen percent of the vote.

The result was that with 17 percent, Jean Marie Le Pen of the National Front came in ahead of all leftist candidates and faced President Chirac in the second round of the election. That election was scheduled for two weeks later. As Mr. Zemmour explains:

Each evening, televisions broadcast archive images retracing the Nazis’ rise to power, the extermination of the Jews, and the Second World War. Schoolchildren poured into the streets, encouraged when not obligated by their teachers, [shouting] ‘Le Pen must be burned.’ The propaganda apparatus worked at full tilt. The entire political class called for a vote for Chirac ‘in order to set a roadblock to fascism.’ Every union, every company, every authority appealed to save the Republic: bishops, rabbis, imams, professional athletes, actors, magistrates, attorneys, free masons, the anti-racist leagues, the homosexual movement, even Judge Halphen [who was investigating President Chirac for financial misdeeds] added his little appeal!

The only man to retain his sanity was France’s outgoing Socialist prime minster, who later acknowledged that the country had never experienced any fascist threat, that the National Front was not a fascist party, and that the whole pretence had been nothing but political theater.

On May 5, left-wing voters showed up at polling stations with clothespins on their noses to choose the merely conservative Gaullist candidate over the supposed fascist. Crook or not, Jacques Chirac was reconfirmed as President of the Republic with 82 percent of the vote. The propaganda onslaught had succeeded.

The suburbs burn

On October 27, 2005, two teenagers in Clichy-sous-bois, a suburb of Paris populated almost entirely by African immigrants, fled from a police car making its usual rounds. It is unknown whether they had something to hide or simply wanted to avoid a possibly time-consuming encounter with the police. They hid in a large electrical transformer, where they were electrocuted.

The usual riots broke out. Cars, buses, schools, and gyms were torched. But this time the violence did not stop after a few nights. “Molotov cocktails, manhole covers and washing machines were thrown from the tops of apartment buildings,” writes the author, since “all means were fair for chasing away the helmeted enemy — the French police.” Televised images of the riots became models for immigrants in other suburbs, and the violence spread to more than 274 French towns. “There were no organizers, no representatives, no slogans, no demands, no ideology or party: only the joy of destruction and fighting.” It was an impressive record: 8,973 cars burned, 2,888 arrests, 126 police and firefighters injured, two people killed. Mr. Zemmour reports that the damage was estimated to have cost €200 million.

French Minister of the Interior Nicolas Sarkozy had coincidentally chosen the day before the teenagers were electrocuted to speak to the French inhabitants of another Paris suburb plagued by immigrant lawlessness: “You’ve had enough of this riffraff (racaille) haven’t you? We’re going to get rid of them for you.” The French political establishment, especially his own party, panicked and denounced him. Yet the celebrated riffraff remark — quietly supported by millions of ordinary Frenchmen — may have been responsible for Mr. Sarkozy’s election to the French presidency in 2007. President Sarkozy had five years to deliver on his promise, but when he stepped down the riffraff were still there.

Today and tomorrow

They are there to this day, warns Mr. Zemmour, and growing in number. The suburbs where they live are governed not by French officials but by Islamic caïds (leaders) who apply sharia law — including the death penalty. The only limits to caïd power are set by powerful drug lords no one can afford to offend.

The media report that hundreds of “Frenchmen” have gone to Syria to fight for the Islamic State.

Opposition to the present French regime and the demographic replacement it has promoted is agonizingly slow to gather — but it is gathering. In 2012, Marine Le Pen did slightly better in the presidential elections than her father had ever done, and her popularity continues to increase: In the late summer of 2014, polls showed that if elections were held today, she would be elected president of France.

The success of Mr. Zemmour’s book is itself a sign of hope; at the French Amazon site, it has slipped to number two, but only behind a silly €3.00 pamphlet that makes fun of motherhood. It is miles ahead of anything else that even remotely resembles thoughtful non-fiction. The Suicide of France can be seen as a French counterpart to Thilo Sarrazin’s bestselling 2010 book, Germany Abolishes Itself.

Mr. Zemmour himself makes no predictions and offers no solutions. The question remains whether patriotic opposition can overthrow the current establishment in time to save the historic French nation — or even to head off a bloody civil war.

- Post TagsBook Review, Classics, Common Sense in High Places, France, Immigration, Islam