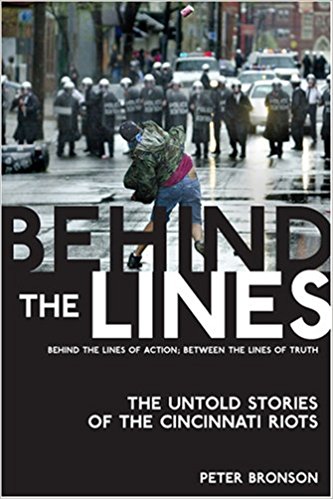

Peter Bronson, Behind the Lines: The Untold Story of the Cincinnati Riots, Chilidog Press, 2006, 152 pp.

The Cincinnati riots of 2001 were the worst racial violence the United States has seen since the Los Angeles riots of 1992. For three days, blacks burned, looted, and wrecked some 120 business, at an estimated cost of $14 million. The police made 600 arrests but, astonishingly, there were no deaths.

Peter Bronson, a veteran journalist with the Cincinnati Enquirer, has written what is probably the only book-length account of riots. He pulls no punches. This is a frank account of how Cincinnati capitulated to blacks, betrayed its police, and paid for its cowardice for years afterwards. Needless to say, this book has been largely ignored.

One of Cincinnati’s worst neighborhoods is known as Over-the-Rhine. In 1850, it was a bustling German immigrant community of 43,000 people. In 1990 it was 71 percent black and, like so many ghettos, its population had plummeted to about 10,000. By 2001 it was a hive of crime, drugs, welfare, and hatred of the police.

Mr. Bronson points out that Cincinnati’s white power structure had unwittingly stoked feelings of grievance and lawlessness. During the five years leading up to 2001, Mr. Bronson’s own paper, the Enquirer, had published at least a dozen major stories criticizing the police as potentially racist and violent.

Democratic politicians had pushed Cincinnati even further: They had let protesters crowd into city council meetings, where they shouted about “oppression” and “white devils.” The rowdies were black, so council members feared accusations of “racism” if they asked police to maintain order. These disruptions — the significance of which became clear later — were broadcast to astonished citizens over public-access television.

The conventional view, which Mr. Bronson considers simple-minded, is that the riots were touched off by a police shooting. It is certainly true that at 2:20 a.m. on Saturday morning, April 7, 2001, white officer Stephen Roach shot and killed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas in the worst part of Over-the-Rhine. Thomas had more than a dozen outstanding warrants — though none was for a violent crime — and was running from the police. He and Officer Roach came racing around a corner towards each other almost simultaneously, and the policeman fired. When, moments later, other officers ran up, the first words out of a pale and shaken Mr. Roach were, “It just went off.” Mr. Bronson thinks the man probably panicked. Shortly afterwards, however, Mr. Roach claimed Thomas reached down to hike up his trousers and he thought Thomas was going for a gun. Maybe Thomas did reach for his pants. In any case, he was unarmed.

Word of the shooting spread quickly, but as Mr. Bronson notes, there was no rioting on Saturday or Sunday, and none until late Monday. He argues that it was what happened in the interval that lit the fuse.

One key actor in the crucial early moments was the number-two man in the police department, Assistant Chief Ron Twitty. He was an affirmative-action black who had vaulted over the heads of white officers to the highest position ever held by a black in the department. It was an open secret that his work was poor and that others had to cover for him. He had banged up his police cruiser several times and tried to hide the fact (he was finally forced out of the department in 2002 for yet another wreck). He was more of a community liaison — and not a very good one — than a police commander.

The chief of the department, Tom Streicher, was out of town that weekend, so the assistant chief was in charge. When Chief Streicher returned on Monday after the Saturday shooting, he was astonished to learn that his deputy had not called a press conference to discuss the incident and deny rumors. Temperatures were rising, black radio was broadcasting accusations of cold-blooded murder, but the department had done nothing. Assistant Chief Twitty would stumble even more seriously later on.

Mr. Bronson notes that what did happen on Monday probably contributed as much as anything to the rioting. That morning there was a meeting of the city council’s Law and Public Safety Committee at city hall. The committee chairman, a young white liberal named John Cranley, realized that any meeting about police business would attract an even angrier crowd than usual, but specifically ordered that no officers be present for fear they might upset blacks.

A huge mob packed the room, spilling out of the spectators’ area and surrounding the committee members. One man in yellow-and-black African robes carried a huge sign that said, “Stop Killing Us or Else.” He brandished it so close to committee members they flinched and dodged to keep from being hit. The crowd set up such a din that Chairman Cranley could hardly be heard through his microphone. He tried to recess the meeting, but the crowd ignored him. He got up to leave but was jostled and intimidated, and returned to his seat. “I can’t deal with this,” he said, thinking his mike was off.

Instead of calling officers to clear the room, Chairman Crowley turned the mike over to the protesters! Most of the time, there was so much yelling that harangues about “all the brothers who have been shot and choked to death by the police” were inaudible.

Every American city has its equivalent of Al Sharpton, and Cincinnati’s was Rev. Damon Lynch III, leader of the Black United Front. Nearly three hours into a hopelessly chaotic meeting, Mr. Cranley offered Rev. Lynch the mike. What the preacher said was clearly audible and broadcast to the city on public-access television: “Nobody leaves these chambers until we get the answer. Members of the Black United Front are standing at the doors, because nobody leaves until we get an answer.” The Law and Public Safety Committee was hostage to a minister. The crowd whooped with delight, as shouts of “long, hot summer,” and “we’re gonna tear this city up” filled the air.

But the crowd had been howling for hours and was tired of just talking about action. It wanted the real thing. It soon had enough of Rev. Lynch and began pouring out of the hearing room. On the way out, blacks started breaking windows. Some came back to city hall later and broke some more, for an official count of 200 smashed windows.

Police Chief Tom Streicher believes this pitiful performance showed blacks they could ignore authority. “The antics in council, widely broadcast . . . fueled the riots more than anything,” he says. Mr. Bronson calls the council meeting one of “the great institutional failures” that led to chaos.

Chaos was not long in coming. The mob left city hall and made its way to police headquarters, picking up hundreds of bored, out-of-school black children. Soon there was a crowd of about 1,000 people in front of police headquarters, facing a line of two dozen men in blue. Blacks began throwing rocks and bottles and smashed a window in the police building. Officers were about to wade in and arrest the perp but were shocked to get the order to stand down. Police Chief Streicher was away at an emergency meeting and Assistant Chief Twitty was in charge. He ordered the police to do nothing, while the mob desecrated the monument to fallen officers just across the street from police headquarters. Blacks tore down the flag from the monument, spat and stomped on it, and ran it back up upside down. Rocks, bottles, and curses continued to rain down on the officers.

Then Assistant Chief Twitty actually did something. He went outside the building and called for a bullhorn. He put in new batteries to make sure it was working — and then turned it over to the rioters. Mr. Bronson writes that Cincinnati police are furious about this to this day. They were expecting him to try to disperse the mob; instead he gave a symbol of police authority to men who used it to call for violence. By the time Chief Streicher got to headquarters all the windows were smashed, the doors were broken, and a black was still shouting into the bullhorn with Assistant Chief Twitty by his side. The chief pushed out the rabble with mounted police and cleaned up stragglers with tear gas.

Many studies have concluded that an early show of overwhelming force usually stops riots. A SWAT team officer who was at headquarters that day is convinced the Twitty approach was the worst possible way to handle the demonstrators. “There were no consequences for their actions, and they could see that,” he told Mr. Bronson. “It just made it worse.” Twice that day, blacks had made a mockery of authority; it was a prelude to the real violence that followed.

Property and whites

For the next two days, the mob had two targets: property and whites. Egged on by black radio and even white media that spoke of “insurrection” and “uprising” rather than “mob violence,” blacks surged through downtown, looting and burning. Police fired beanbag rounds from shotguns and secured one block only to see looters move on to another. The police were dodging live fire, and one officer miraculously escaped injury when a bullet bounced off his belt buckle, but police did not fire a single lethal round in return.

Rioters attacked whites by blocking intersections to immobilize cars. They would then smash a windshield, drag out the terrified whites, and beat them. Police probably saved dozens of lives by speeding to the scene, clearing out rioters with beanbag rounds, collecting the victims, and getting out before the crowd could regroup and overwhelm the police.

Mr. Bronson writes that the media were virtually silent about the racial angle, which made things worse. Many victims were whites from out of the area who had driven in to “see what a riot is like.” Honest reporting would have kept them away. Instead, newspapers ran big photos of blacks showing bruises from beanbag rounds, and gave the impression the police were causing the violence by firing at random.

The cruelest insult came from the city. After the first day of riots, when officers staggered home after 16-hour shifts, they learned that Mayor Charles Luken had gone on CNN to say: “There’s a great deal of frustration within the community, which is understandable. We’ve had way too many deaths in our community at the hands of the Cincinnati police.” Even the mayor was saying police were responsible for the riots. Mr. Luken later acknowledged he had behaved stupidly: “I wish to hell I had never said that,” he admitted to Mr. Bronson.

The national media picked up the idea that Cincinnati police had a brutal record of killing blacks, and the myth of “15 black men” who had “died in police custody” swirled from coast to coast. Time magazine called Cincinnati “a model of racial unfairness.” As the police belatedly pointed out, hardly any of the 15 who died were “in police custody.” They were trying to kill policemen, and were shot by officers who feared for their lives. The national media did not care. America was witnessing an “uprising” over discrimination, poverty, and joblessness.

On Thursday, after two days of severe rioting, the mayor finally did what police had been recommending and ordered a curfew. Violence dropped sharply and Friday was peaceful. The next day, however, brought another nasty incident. Exactly one week after the shooting, there was a mass funeral for Timothy Thomas at Rev. Damon Lynch’s church in Over-the-Rhein. Kweisi Mfume, then head of the NAACP was there, along with one of Martin Luther King’s children and — to the shock and disgust of the police — Ohio governor Robert Taft and his wife, Hope. “He never once came to a police funeral,” says SWAT officer John Rose. “And here he was, going to this.”

Needless to say, all Governor Taft and his wife got was a humiliating earful about white wickedness from Rev. Lynch, but his presence in the middle of what had been a riot zone was a security nightmare. Despite their contempt for his gesture of solidarity with a black criminal, police had to be sure his limo was not stopped and attacked.

As the funeral broke up and people poured into the streets, a band of out-of-town blacks unfurled a banner, blocking an intersection. Six officers responded as they had during the riots, clearing the intersection with beanbag rounds to make sure the governor could get through if he had to come that way. Several of the demonstrators claimed they were injured by “excessive force” — the police believe the ringleader was cut by a bottle thrown by demonstrators — and the city handed over $235,000 in damages. The mayor himself called for a federal investigation of “the Beanbag Six,” which found — years later — that they had done nothing wrong.

Mr. Bronson notes that the city acted just as cravenly after the riots as before. Whites were yearning for “root causes” to put right and for “programs” that would make blacks happy and grateful, so Cincinnati went down a well-worn path: “appoint a commission, blame white society, then ignore the findings and argue about them, while waiting for someone who is honest and brave enough to point out that riots are caused by rioters.”

In the process, the city agreed to outside monitors and inspectors who would supervise the police and reform the city. It spent $10 million on “so-called solutions, lawsuits, court hearings and reports.” Mr. Bronson heaps scorn on the overpaid mooncalves who were supposed to teach old pros like Chief Streicher how to run the police department. It was like “trying to reform the Marine Corps with experts from the Salvation Army.” The politicians never turned the spotlight on themselves, or on the disastrous committee meeting at which blacks made a mockery of authority and broke out windows at city hall. The cowards blamed the people who showed real courage: the police.

Officers reacted as they usually do when they risk their lives for a city that turns on them. Many veterans left the force. Those who stayed stopped taking risks. Why collar and frisk a probable black criminal when there was a good chance Rev. Damon Lynch would screech about “racial profiling” and the city would side with the criminal? Police spent less time in Over-the Rhine, and just three months after the riots, arrests were down 30 percent; shootings were up 600 percent. Murders soared to new records. It was several years before Chief Streicher could get the men to put their hearts back into police work.

Another consequence of the riots could have dealt the city a blow from which it might not have recovered. Rev. Lynch, unsatisfied with the pandering, urged all black and black-sympathetic organizations to boycott Cincinnati. “Police are killing, raping, planting false evidence,” he explained, “and are destroying the general sense of self-respect for black citizens.” For months, the media handed him the biggest megaphone in the city, giving him more air and press time than the mayor. A host of performers, including Bill Cosby, Whoopi Goldberg, Wynton Marsalis, and Smoky Robinson canceled appearances. The city is thought to have lost at least $10 million from conventions and conferences that stayed away.

Loss of revenue came at a bad time. With downtown already jumpy because of riot scares and the police slowdown, some of Cincinnati’s landmark businesses closed. For a time, the city seemed to be headed towards the permanent desolation of Detroit and Akron. If the black population had been larger the city might have died, but Mr. Bronson says it has pulled out of its nosedive. He writes that the election, in 2006, of a city council that appreciates the police was a big step back from the brink.

It was of course the police, during three days of pitched battles, who saved the city, but all they got was blame. “Never, ever was there said a single word of gratitude to us for anything,” Chief Striecher explained afterwards. “Quite honestly, we never expected it. We knew we would be chastised and publicly humiliated by city council.”

What lessons does Mr. Bronson draw from the riots? One is the terrible damage done by his own profession. Time and again, the press blamed police and excused rioters, and never seemed to realize it was fanning the flames. “The media are playing a largely overlooked role as agitator and inciter,” he writes. Like the whites in city government, they could not set aside “the belief that all black grievances are legitimate and must be assuaged at all costs.”

The unspoken message of this book is that authority figures must show backbone. They should never have let blacks turn city council meetings into shouting matches. They should never have appointed an incompetent assistant police chief just to placate blacks. They should have clamped down at the first sign of lawlessness rather than fret about provoking a reaction. The Cincinnati riots were just one chapter in the much larger story of the decades-long demoralization of the entire country.

This sobering book is not without redemption, however. Officer Stephen Roach went on trial in September 2001 for negligent homicide and, to the astonishment of Chief Striecher, was acquitted. (It was a bench trial; he probably could not have gotten a fair jury in Cincinnati.) He went on to take a police job in the neighboring town of Evandale, where he became an honored and even much-commended member of the force.

America is supposed to be the land of second chances. Will Cincinnati — and the nation — get a second chance?