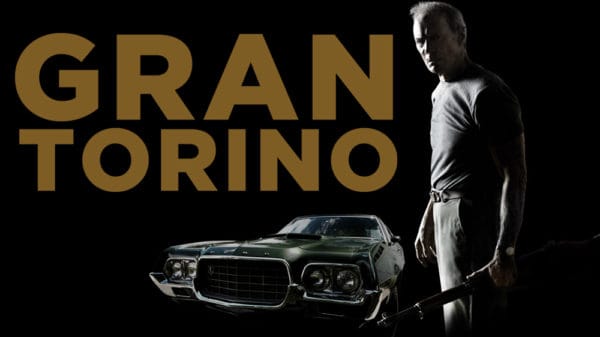

Gran Torino, screenplay by Nick Schenk, produced, directed, and starring Clint Eastwood, Warner Brothers Pictures DVD, 2008, 116 minutes, Rated R.

Clint Eastwood has starred in many memorable films since the 1960s as the strong, silent, violent hero. He has also directed several movies, two of which, Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby, won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director. He remains best known, however, for his role as “Dirty Harry” Callahan, the fearless, .44 magnum-wielding San Francisco police inspector. Gran Torino was rumored to be the final Dirty Harry film, with the Callahan character in retirement. It isn’t, but there are similarities between Dirty Harry and the hard-bitten character he plays here.

At its best, this movie convincingly portrays the dispossession of white, middle-class America, but it is ultimately dishonest: At the end we are to believe that although immigrants are alien to begin with, they will soon become good Americans — perhaps even better Americans than whites.

Mr. Eastwood plays Walt Kowalski, an aging, embittered blue-collar worker who spent most of his life working on an assembly line at a Ford plant. He is also a decorated combat veteran of the Korean War, and remains tormented by his wartime experiences. He lives in a close-in Detroit suburb, the only white man left in what was once a white, working-class neighborhood. His new neighbors are an extended family of Hmong refugees from Southeast Asia.

Mr. Eastwood is a skilled filmmaker, and he conveys Walt’s sense of isolation effectively. The Hmong are poor and strange. The parents do not speak English and do not maintain their houses. Walt’s house is by far the best kept in the neighborhood, and the only one that flies an American flag. He is clearly the alien here, a point reinforced by the matriarch of the next-door Hmong family, who wonders outloud why he is still hanging around after all the other Americans have moved away.

We learn all we need to know about Walt Kowalski and his own family in the first few minutes. The film opens with the funeral of his wife. He is stiff and uncomfortable, and shakes his head in disgust as his grandchildren file in, inappropriately dressed and disrespectful. His two adult sons and their families are vapid, materialistic yuppies, interested in Walt only if they can get something from him. Toward the end of the film, Walt clumsily tries to reach out to his eldest son, but is — predictably — rebuffed.

Walt’s racial views reinforce the stereotype of an elderly white, working-class man. Walt is a racist simply because, well, he is a white, working-class man, and that’s how Hollywood sees them all. He makes derogatory remarks about everyone, and has many colorful slurs for his Asian neighbors (gooks, slopes, zipperheads, Chinks, swamp rats, egg rolls), his Italian barber and friend (Doo-wop, Dago, Guinea), his Irish contractor friend (drunken Irishman and Mick) and of course, blacks (just spooks — apparently “nigger” is too naughty, even for Walt).

Clint Eastwood (Credit Image: Thore Siebrands / Wikimedia)

This is supposed to show Walt as a product of his times, a man stuck in racist 1950s America, but only in Hollywood do white working-class men speak that way. Walt Kowalski is an updated version of Archie Bunker, who was also an angry, racist white veteran (of the Second World War).

But just as Walt has trouble with his children, so do the Vang Lors, the family next door. The mother is a recent widow, and she worries that her son, Thao, will be caught up in a Hmong gang. Thao’s attempts to escape from its clutches are the main story line of Gran Torino.

As part of his initiation into the gang, Thao is supposed to steal Walt’s prized possession, the 1972 Gran Torino Sport Coupe that gives the film its name. Thao bungles the theft and wakes up Walt, who grabs his M1 Garand rifle but bungles the collar, and Thao gets away.

A few days later, the gang comes by the Vang Lors’ house to give Thao a second chance. His family refuses to let him go with them, and there is a fight. When it spills onto Walt’s yard, he storms out of his house with his M1 and orders the gangbangers off his property. Caught unarmed, they slink sullenly away.

His Hmong neighbors now see Walt as a hero and begin leaving food on his doorstep, much to his consternation. Walt just wants to be left in peace so he can spend his final days drinking beer on his porch, but the Hmong now feel indebted to him. Sue, the feisty and sassy Hmong teenage daughter, and her mother bring Thao over to make him apologize, telling Walt that the boy dishonored the family by trying to steal his car and must work off the debt.

Walt wants nothing to do with Thao, but in true Hollywood style, Thao is a hard worker who wins Walt’s grudging respect and affection. The transformation of Thao into an inter-racial surrogate son will come as no surprise to people who remember the plot of the 1970s television sitcom Chico and the Man, which starred Freddy Prinze and Jack Albertson in roles similar to those of Thao and Walt.

Walt’s relations with his own family continue to be rocky, but he draws closer to the Vang Lors. He rescues Sue from blacks who want to rape her, and is invited to Hmong family celebrations. He drinks foreign beer, learns to like Hmong food, and chats with a Hmong teen-aged girl who treats him respectfully, unlike his own granddaughter. His surrogate fatherhood deepens as he sets about “manning up” Thao. He gets him a job, lends him tools, and imparts to him the wisdom he would have liked to pass on to his sons and grandsons, if only he had had a relationship with them.

Gran Torino (2008) – Clint Eastwood, Bee Vang, Ahney Her, and Brooke Chia Thao. (Credit Image: Double Nickel Entertainment / Gerber Pictures / Malpaso Produc./ Rivetti, Anthony Michael / Album)

But the gang has not forgotten about Thao, and the violence ratchets up. Walt tries to protect his neighbors, but he is not Dirty Harry. His violence doesn’t solve problems; it makes things worse. The gang shoots up the Vang Lors’ house, kidnaps Sue, and beats and rapes her. Thao expects Walt, the tough, rifle-wielding ex-soldier, to deliver vengeance, and the stage is set for the final, predictable confrontation. Walt is heroic, but not in the predictable way.

There are two themes running through Gran Torino. The first is the corrosive effect of violence. Clint Eastwood has portrayed many violent men over the years, and in the Sergio Leone films, his character used violence casually, self-servingly, and not really in the name of justice, but effectively. Violence is how tough men on a lawless frontier survive. In the Dirty Harry films, violence serves justice. Harry Callahan confidently dispatches criminals who clearly deserve to die.

In Gran Torino, violence begets nothing but more violence. There is a message here that is missing from Mr. Eastwood’s earlier films: violence corrupts.

Walt is tormented by Korea. He won the Silver Star for wiping out a Chinese machine-gun nest, but he killed unarmed Chinese soldiers who were trying to surrender. At one point in the film, Sue calls Walt a good man, but he thinks of himself as a murderer. Walt sees the violence he unleashed with the gang spiral out of control, but he finally ends it through sacrifice, not violence. Gran Torino can almost be seen as an atonement for all the killing in Mr. Eastwood’s earlier films, and he must have been disappointed that it was snubbed at the Academy Awards.

Or perhaps Mr. Eastwood no longer has Harry Callahan’s moral confidence because Dirty Harry’s world no longer exists. The far more interesting theme of Gran Torino is white displacement. Walt Kowalski is part of Harry Callahan’s America — white America — but that America is gone.

The rules no longer apply. Walt Kowalski played by those rules. He fought America’s wars, built its cars, kept his nose clean, raised a family, bought a house, maintained it, and for what? To give it away to aliens? His reward for trying to preserve order in his neighborhood is — at first — to be despised by the newcomers.

(Credit Image: Double Nickel Entertainment / Gerber Pictures / Malpaso Produc./ Rivetti, Anthony Michael / Album)

His trim house and his tidy lawn are an affront to the Vang Lors and the other Hmong. He shames them, because they cannot do what he can. He can fix his house, maintain his lawn, and impose order — with a rifle, if necessary. They can do none of these things, and are at the mercy of forces they cannot control: weeds, dry rot, peeling paint, gangs. Walt is the white man who builds things, keeps order. They are Third-Worlders, who get pushed around.

But Walt, too, now faces a force he cannot control: demography. His house will pass from the white world to the non-white world. No white family will live in it after he’s gone. It is only a matter of time. The Hmong granny realizes this, which is why she calls him a stubborn white man and a dumb rooster. He’s trying to fight something he can’t control.

Walt loves his neighborhood, though, which is why he didn’t leave in the first place. He teaches Thao how to fix things and shows the Hmong they can take care of their houses. He tries, single-handedly, to get rid of the gang. Since he can’t make his neighborhood more white, he tries to make his neighbors more white, and that is what the film is really about: white America graciously giving way to its non-white future. This is clear at the beginning, as Walt buries his wife while the Vang Lors welcome a new baby into their home.

We shouldn’t be bothered by this, the film tells us, because the people replacing us will be just as good, if we only help them a little — a sort of cultural affirmative action. They may even be better. They would never play a video game at their grandmother’s funeral, as Walt’s grandson does. They value tradition and family more than we do. They would never try to push old folks off into a retirement home the way Walt’s son does. Their religion is not cold and formal, like the Catholic ceremony that opened the film, but warm, and people-centered.

This is the movie version of the standard Republican line on immigration: We should let the non-whites in because they are younger and more vibrant and have better family values. Walt’s — and the movie’s — true revelation is that he likes the Hmong family more than he likes his own children.

What is worst about this film is a vague undercurrent of dishonesty. The way Mr. Eastwood presents his characters and their post-industrial Detroit leaves the impression that he knows the score, that he knows what is replacing white America will not be better, but cannot say so. He would lose his post-Harry Callahan respectability. Instead we are left with stereotypes and clichés recycled from old television programs. Walt Kowalski isn’t Dirty Harry; he is Archie Bunker with an M1 Garand and a death wish. Even the ending is a cliché: Walt’s feckless granddaughter, who covets the Gran Torino, doesn’t get it. Thao rides off into the sunset in Walt’s one abiding love.

- Post TagsClassics, Hmong, Immigrants, Movie Review, Racial Conflict