Taymaz Valley, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

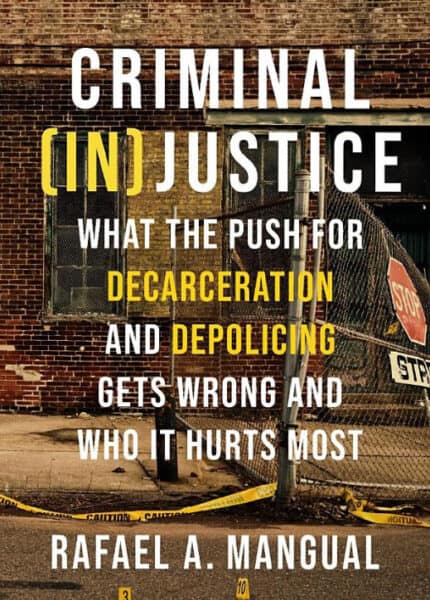

Raphael A. Mangual, Criminal (In)Justice: What the Push for Decarceration and Depolicing Gets Wrong and Who It Hurts the Most, Center Street, 2022, 256 pages, $29.00 hardcover

First-time author Rafael A. Mangual is a son of Dominican and Puerto Rican parents. Trained as a lawyer, he now is a public policy analyst with the Manhattan Institute and contributing editor to its flagship publication City Journal.

Mr. Mangual lived to the age of nine in a sketchy Brooklyn neighborhood, at which point his NYPD-detective father decided to move the family to an overwhelmingly white Long Island suburb. The boy did not like the change at first, and was teased for looking different from other kids. Gradually, however, he came to realize that, unlike in his old neighborhood, there was almost no risk of having his bicycle stolen from under him: “I grew to understand and appreciate the decision my parents made to move my sister and me out to what they felt would be a safer, more nurturing environment.” Now a father of two, he recently made a similar move for his own children.

Mr. Mangual was inspired to write Criminal (In)Justice by the madness that gripped America in the wake of George Floyd’s death. Affluent liberals cavalierly pressed for policies whose negative consequences will be borne by poor people in neighborhoods they never visit. Politicians rushed to pass ill-considered police oversight and reform laws on the assumption that sensational stories of police shootings were reliable evidence of a need for thoroughgoing changes. As the author writes: “The road to productive reform begins not with a rush forward, but with a step back — one that allows us to soberly consider the complicated realities that our passions may be obscuring.”

We have been here before

Older Americans may get a sense of déjà vu from today’s debates. The 1960s and 70s saw rising crime, accompanied by much uninformed talk about the need to combat its “root causes,” alleged to be poverty and deprivation. Such talk did not go unanswered: Criminologists did empirical studies of correlations between crime and various forms of adversity. The result was extensive documentation of a relative lack of correlation. It became known as “crime/adversity mismatch,” and can be read about in studies such as Barry Latzer’s The Rise and Fall of Violent Crime in America (2016). Between 1950 and 1970, for example, the material welfare of black Americans improved greatly, but their crime rates rose.

Meanwhile, scholars such as James Q. Wilson (an important influence on Mr. Mangual) were building a powerful case for combatting crime directly, i.e., without fussing over alleged “root causes.” One idea Wilson advocated in the early 1980s has become known as “broken windows theory.” At that time, many police departments did not bother enforcing laws against lesser public order offences (such as leaving broken windows unrepaired) on the plausible grounds that resources were already being stretched trying to stop serious crimes. Wilson and others proposed that combatting lesser offenses would reduce serious crime as well.

Within a few years, NYPD Chief Bill Bratton made broken windows theory the basis for a reform of New York policing. He also started active “stop and frisk” in the most dangerous neighborhoods with the idea of combating crime before it happened. His reforms coincided with a nationwide trend toward less lenient treatment of criminals, including mandatory minimum sentences and three-strikes laws. The result was a historic drop in crime during the 1990s that continued into this century — and was very noticeable in New York City.

The very success of these reforms helped inspire a counter-movement to undo them. America’s incarceration rate had become the highest in the world, and critics cited falling crime rates themselves as evidence that this level of incarceration was unnecessary. Getting tough on crime had also meant getting tough on black and Hispanic men, so complaints of racial bias came early and loud. Others argued that most prisoners were nonviolent drug offenders who should not be jailed, or that jailing fathers tore families torn apart and hurt children.

Groups representing an anti-fascist ideology, including a defund the police group, build a revolutionary workers state and a group against the Proud Boys, marched form Central Park South towards Madison Square Park. (Credit Image: © John Lamparski/SOPA Images via ZUMA Wire)

The tone of these arguments was often much less polite than my summary. As Mr. Mangual puts it, Americans have seen “elected officials, media figures, and activists viciously demonize the institutions that played central roles in the public safety gains.” Much of the reformers’ anger was due to sensational media reports about black criminals either shot by police or who died in police custody: Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Walter Scott, Freddie Grey, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and George Floyd.

The decarceration movement took hold even before the hysteria that followed Floyd’s death: Between 2009 and 2019, America’s imprisonment rate declined by 17 percent. Not coincidentally, crime began climbing. Crime historian Eric Monkkonen has speculated that cycles of higher and lower crime rates may be natural: “[R]ising violence provokes a multitude of control efforts, [but when] the murder rate ebbs, control efforts get relaxed, thus creating the multiple conditions causing the next upswing.”

Answering the critics

Antipolice zealots are not the only people who notice that America has the highest incarceration rates in the world. However, the West European nations to which America is often compared have incarceration rates so low that we would have to release 70 percent of inmates to reach parity. Brazil is a country with more crime than America, but it also has lower levels of incarceration. This is easily explained by Brazil’s relative poverty; it does not have the same resources for law enforcement we do. America has a high incarceration rate because we have both relatively high crime and the money to deal with it.

It is not true that most prisoners in the US are nonviolent drug users: most are violent offenders who have already had repeated second chances. Just 14.1 percent of prisoners are in for drug offences, mainly trafficking. Fewer than 4 percent of inmates are in for simple possession and that charge often understates the crime. Ninety-five percent of state-level criminal cases are resolved by plea bargain, meaning that more serious charges are dropped in exchange for a plea to lesser charges. Some prisoners go to jail for drug offenses the way Al Capone did for tax evasion: not because it was his most serious crime, but because it was the charge that would stick. Moreover, since criminals are not specialists, the nature of their most recent offence is not always a good clue to what crime they will commit next.

One of the odder arguments for reform is that incarceration “tears families apart.” Fatherlessness is certainly a problem in America, but it is overwhelmingly caused by divorce or illegitimacy, not incarceration. Moreover, men incarcerated in America typically belong to that minority whose children are better off not being in close contact with them.

The most common attributes of criminal offenders include a grandiose sense of entitlement and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). A sense of entitlement means an “unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations,” and often comes with “a highly antagonistic approach toward interpersonal dealings.” It is among the best predictors of many forms of aggression. ASPD can be defined as “deceitfulness, impulsivity, reckless disregard for others, high levels of irritability and aggressiveness, and remorselessness in the wake of misbehavior.” Two to four percent of men have this disorder. Among inmates, it is 40–70 percent.

Mr. Mangual cites studies to show that the “quality of a father’s involvement matters more than his mere presence,” and that children who live with fathers who “engage in very high levels of antisocial behavior” will go on to behave “significantly worse” than “their peers whose fathers also engage in high levels of antisocial behavior but do not reside with their children.” Bad parents can leave children “traumatized, empty, and incapable of forming meaningful personal relationships,” which makes them more likely to become criminals.

Mr. Mangual’s discussion reminded me of the furor during Donald Trump’s presidency over separating illegal aliens from their children at the Mexican border. Why do some people seem to care about family breakup only when it is because parents broke the law?

Criticism of racial disparities in incarceration is, of course, a staple of calls for reform. A well-known example is Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010). Such disparities are easily explained by racial differences in criminal behavior, and these arguments usually ignore racial differences in victimization.

Serious violent crime in America is heavily concentrated, geographically and demographically. Criminologist David Weisburd has even tried to formulate a “law of crime concentration:” Somewhere around 4 percent of a city’s blocks will usually see 50 percent of its total crime. Most of the people living in these neighborhoods are not themselves violent criminals; they are just too poor to move away. These are the people most vulnerable to the effects of violent crime and about as disproportionately black and brown as the criminals themselves. They are the ones who pay for the reckless decarceration promoted by limousine liberals.

Limitations of post-Floyd police reforms

In April 2021, the New York Times reported that “over 30 states have passed more than 140 new police oversight and reform laws” after George Floyd’s death. Mr. Mangual believes that most reforms have been ill-considered, for two reasons: 1) legislators have overestimated the problem of excessive police force, and 2) have assumed that ready-made solutions are available for real problems.

Between 2015 and 2020, police in the US shot and killed an average of 993 people a year. This must be understood in a context in which nearly 700,000 full-time police officers interact with over 61 million persons and make over 10,000,000 arrests every year. Moreover, 93 percent of fatal shootings involve armed suspects. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), claims of excessive force occur at a rate of only about one per every 200 full-time officers per year, and BJS found that civilian complaint review boards uphold just 6 percent of claims of excessive force. In short, the author writes, “there is much less room for improvement than one might guess after consuming the mainstream media narrative about policing in America,” and we must remain “sober and realistic about how much we can expect to reduce an already exceedingly rare occurrence.”

Mr. Mangual lists five common proposals for police reform: 1) defunding, 2) demilitarizing, 3) abolishing qualified immunity for officers, 4) diverting some police calls to mental health professionals, and 5) training officers in de-escalation techniques.

1) The most foolish reform proposal is surely defunding. As Mr. Mangual notes, the inverse correlation between policing and crime is about the most robust finding in all of criminology, and cutting back on police “will result in the deaths of a hell of a lot more people than police kill.” Those who profess concern over black lives may wish to note that black homicide victim numbers go down at about twice the rate of whites as police forces are strengthened.

2) The seeming militarization of American police forces has disturbed many Americans: Officer Friendly has given way to faceless men in black tactical gear. This is mainly due to the increased prevalence of SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) teams and to the introduction, since 1990, of the so-called 1033 program under which state and local law enforcement can acquire surplus military equipment.

Oregon Department of Transportation, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

However, Mr. Mangual demonstrates both that SWAT teams are responsible for a very small fraction of police violence, and that overall police use of force has actually declined since the start of the 1033 program. In 1990, for example, NYPD officers shot and injured 72 people, already a steep decline from the 1970s; by 2019 the figure was 13. Chicago and Los Angeles also experienced marked declines during these same years that police were being “militarized.” Also, the more intimidating appearance of today’s police has what criminologists call “perceptual deterrence.” In short, “demilitarization” — cutting down SWAT deployments and the use of military gear — wouldn’t make significant reductions to the already rare use of force by police.

3) Qualified immunity is a legal doctrine that “protects state actors (not just cops) from being sued in their personal capacity for violating constitutional or statutory rights that were not established at the time those actors engaged in the conduct in question.” Obviously, it would be very unusual, after a police action, for the law or a ruling to be changed in ways that would make the action retroactively illegal. As Mr. Mangual notes, this defense often amounts to “relying on minor factual distinctions to set the case in question apart from controlling precedents,” which “gives critics of qualified immunity a legitimate beef.” However, one study found that qualified immunity defenses were successful in fewer than 4 percent of lawsuits, and Mr. Mangual argues that “the role the doctrine plays in modern police litigation is drastically overstated.”

The main source of liability protection for police officers is not qualified immunity but indemnification. The overwhelming majority of officers work in jurisdictions that indemnify them against financial liability for damages awarded as a result of actions performed on duty. One study found that 99.98 percent of the dollars paid to plaintiffs in such cases were paid by taxpayers, not officers.

4) Big city cops get a fair number of calls about disturbed people, often at odd hours. In New York City alone, 911 operators field about 180,000 such calls every year. These people can be just as dangerous as criminals, but one reform proposal is to send such calls to mental health professionals.

The author’s Manhattan Institute colleague Charles Fain Lehman has studied this, concluding that mental health professionals may help the police in such situations, but are not a replacement. It may not be clear from a call whether the person is a criminal or disturbed; one study found about 20 percent of calls were unclear or misleading. Moreover, the US Department of Health and Human Services is now forecasting a shortage of mental health professionals. As Mr. Mangual puts it, “there just isn’t a pool of qualified people willing to work all hours of the day to respond to volatile situations, many of which will end up requiring the use of force by police anyway.”

5) De-escalation has been tried as an alternative to control and restraint if someone is having a mental health crisis. Some propose that the police should use it, but evidence for the superiority of de-escalation to restraint is weak even in mental health. It is possible such strategies could work in some law enforcement situations, but that is unproven. Any improvements are likely to be marginal, both because violent incidents are relatively rare and because de-escalation takes time while police must often make very quick decisions about use of force.

Profiling and stop and frisk

As mentioned above, New York City’s dramatic drop in crime in the 1990s was in part due to “stop and frisk” in the most crime-ridden neighborhoods. This involves questioning and sometimes searching passers-by for drugs, weapons, or evidence of criminal activity. The great majority of such searches yield no results: One study conducted in Boston found that only 2.5 percent uncovered contraband. Stop and frisk certainly inconveniences a lot of innocent people, many of whom say the experience was humiliating. And of course, plenty of young black and brown men are among those inconvenienced or humiliated. This is to be expected in those neighborhoods.

But here again, Mr. Mangual offers useful context. He describes how, as teenagers and young men, he and his Latino friends took pleasure in intimidating white neighbors with gangland-style clothes and tough posturing. He recalls that most of his friends were decent kids beneath the surface, but they did not want to appear “clean-cut.” This is a normal part of life in the urban jungle. Young men are always trying to look tough — even dangerous. They may not fully understand their own behavior, but it is rational: The more dangerous they look, the less likely it is that genuinely dangerous people will attack them. Mr. Mangual also said it eventually dawned on him that intimidating dress and behavior are not always an advantage; they can frighten people who could have been helpful — for example, by offering them jobs.

Credit Image: © Nicolas Enriquez/ZUMA Wire/ZUMAPRESS.com

This perceptual arms race between criminals and young men acting tough is something urban policemen see all the time. Obviously, they are most likely to stop and frisk those who most look like criminals, even though many of them are going to be ordinary young black men aping the fashions of “gangsta rap.” Abolishing stop and frisk would avoid inconveniencing or humiliating them, but, as black commentator John McWhorter notes, it would also “leave innocent residents of poor neighborhoods at the mercy of hardened criminals.”

Would it be possible to improve stop and frisk by teaching police to dope out subtle differences between actual criminals and ordinary toughs? Maybe for a while. But word would quickly spread on what makes you really look like a bad dude, and police would be back to square one.

Conclusion

Following the George Floyd riots of 2020, Democrats announced in unison that policing would have to be “reimagined.” The twin assumptions behind this silly language were that law enforcement is rotten with systemic racism, and that sweeping reforms will to set everything right. Both assumptions are wrong. Policing in America dates back to the founding of the NYPD in 1845. In the 177 years since then, an enormous amount has been learned about what works and what doesn’t. Improvements will be matters of detail and at the margins.

The millions of black Americans who believe, in the words of basketball star LeBron James, that the police are “hunting us,” are wrong. The blame lies not with law enforcement but with a media caste determined to promote an absurd narrative of innocent blacks and browns being crushed beneath by an all-powerful white oppressor.

- Post TagsCrime, Featured, Racial Profiling