A Little-Known Chapter in the Muslim War Against the West

- Post AuthorBy Sinclair Jenkins

- Post DateFri Aug 23 2019

Islam is the hereditary enemy of Europe. Since the invasion of Spain by the Moors in 711 until the present day, Islam has tried to dominate Europe and has fought back when it was dominated by Europe. A little-known but bloody chapter in this endless war took place in the aftermath of the First World War. It resulted in the Spanish enclaves in Morocco — Ceuta and Mellila — that are now famous as entry points for thousands of Africans who try to escape the continent by climbing a fence into an outpost of Europe.

After the First World War, all the major European empires faced Muslim insurgencies. Beginning around 1920, Arab fighters inspired by President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” [1] briefly put aside their tribal and sectarian divisions to battle the British and French empires. In British Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq), approximately 131,000 Shia and Sunni tribesmen carried out raids, ambushes, and several sieges on isolated British outposts manned mostly by Indian troops. In one particularly bloody incident in July 1920, tribesmen massacred hundreds of men of the 108th (Indian) Infantry Regiment and the Manchester Regiment [2]. The Empire’s hold on Iraq remained shaky until the British captured the holy city of Najaf in August. Even after this victory, which took five Indian and two British divisions, the newly formed Royal Air Force kept several squadrons in the country and had to drop poison gas on restive tribes.

At the same time, the French were fighting Syrian Arabs. Called the Franco-Syrian War of 1920, the French sent thousands of soldiers, most of whom were a mix of Arab, Senegalese, and French Foreign Legionnaires, to overthrow the short-lived Arab Kingdom of Syria. Several years after the French took Damascus, a new enemy arose — the Druze mountain people. John Harvey, a Welsh coal miner and former British soldier who joined the French Foreign Legion in the 1920s, recounts the ferocious fighting between the legion and the Druze in his book With the French Foreign Legion in Syria.

Harvey says many terrible things about the French and the Foreign Legion, but he reserved most of his venom for the Senegalese. He describes these black soldiers, whom the French used to fight their small wars in the colonies, as less than useless. During the defense of the Lebanese town of Rashaya against a Druze invasion, the “black troops were in a state of hopeless panic” and had to be whipped into the fight by white officers [6]. The only time the Senegalese showed any thirst for action was when they could torture a wounded Arab or Druze. Harvey believed it took France two years to put down the Druze because of the poor quality of West African troops.

Spain also spent the 1920s putting down an Islamic rebellion. By then, Madrid’s colonial possessions were a pale shadow of more glorious days, and northern Morocco was the only field open to imperialist expansion.

Spain has had a long and mostly violent relationship with Morocco. In the early 8th century, Visigoth Spain was overrun by an Islamic army under the command of Arabs but mostly made up of Berber tribesmen native to Morocco. According to historian Dario Fernandez-Morera, the invasion began with a Berber raid in 710. A haul of beautiful Visigothic and Hispano-Roman female slaves inspired the Umayyad governor Musa ibn Nusayr to lead his army into the Christian kingdom the next year [7].

The Umayyad conquest of Spain not only saw an inferior civilization triumph over a superior one (Morera uses Arab, Greek, and Latin texts, plus recent archaeology, to show that the Visigoths were literate and skilled administrators who built fabulous roads and churches all the while maintaining Spain’s Roman heritage), but according to some accounts it was accomplished thanks to treachery by a Byzantine count in North Africa named Urbanus or Julian, along with the Jews of Spain. The Muslim army of conquest left the latter group in charge of captured cities such as Cordoba and Toledo [8].

Visigoth nobles of Asturias and Leon led the first wave of reconquest, and Castile and its ally in Aragon finally expelled all Muslims from Spain in 1492. Despite the current fashion to praise Muslim tolerance and multiculturalism in Spain, Islamic Spain practiced jihad, defined as warfare or violence in the name of Islam. The most vicious Muslim tyrants of Spain were the Berber/Moroccan dynasties of Almoravids and Almohads. The Almoravids expelled the entire Christian population of Andalusia to Africa in 1106 and 1138, while the Almohads exterminated the remaining Christian population of Granada and gave both Christians and Jews the choice of conversion or death [9].

Even before Spain was totally free from Muslim rule, Spanish and Portuguese Christians invaded Morocco. In 1415, King John I of Portugal conquered the city of Ceuta, and it remained in Portuguese hands until it was formally ceded to Spain by King Afonso VI in 1668. Spain conquered the city of Melilla in 1497, five years after King Ferdinand and Isabella completed the Reconquista. These two autonomous port cities continued under Spanish authority until 1860. In that year, Spain won a short war in Morocco that forced Morocco’s sultan to recognize Ceuta and Melilla as officially Spanish. Between 1893 and 1894, Spain once again defeated a Moroccan army, this time demanding that the sultan do a better job of policing the notoriously rough and rebellious Rif Berbers who lived near Melilla.

Spanish expansion in Morocco resumed 1910, when Spain’s Army of Africa extended Melilla’s territory to a piece of the Mediterranean coast called Cape Three Forks. In 1912, Morocco was divided between a large French-occupied zone that included the major cities of Fez, Rabat, and Casablanca, and the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco, which was a thin stretch of coastline connecting Ceuta and Melilla. Two obstacles stood in the way of complete Spanish control over northern Morocco: 1) the corruption and cynicism of the Spanish government and many Spanish Army generals, and 2) the Berber inhabitants of the Rif Mountains, which run East-West along Morocco’s Mediterranean coast.

According to historian David Woolman, the realm of the Rif Berbers is a “land of barren mountains and deserts, rarely unified or pacified, chronically misruled, [and] inhabited by a fanatically xenophobic population made up largely of primitive Muslim tribesmen”[10]. The Rif Mountains in 1920 were an area so rich in tribal blood feuds that most family homes included fortified blockhouses for defense. The Berbers of the Rif were proud of their independence, and unfortunately for the Spanish and French, they were tough soldiers, excellent marksmen, and skilled guerrillas. The Rif Berbers may have been the best insurgents any colonial power faced in the 20th century.

There was also German interference. German steamers landed “1,500 to 2,000 tons” of goods in Melilla alone in 1913 [11]. German merchants mastered Arabic and built post offices, railroads, telegraph lines, and other modern infrastructure for the Rif Berbers. In exchange, German conglomerates wanted the mineral deposits that many Europeans believed were in the Rif Mountains.

The Germans also saw potential allies in the Rif Berbers, and during World War I, German arms and money flooded into the Rif as part of a plan to encourage Moroccan tribesmen to invade French Algeria to the East. France, in response, deployed a majority of its Foreign Legion to Morocco during the Great War, while Britain supported the Spanish as part of its plan to keep the French well away from Gibraltar.

Still, from 1912, when it was officially established, until 1920, the Spanish Protectorate was mostly quiet. The average Spanish soldier serving in Morocco was supposed to believe that “the Moors were sworn enemies of all Christians” and that Madrid was a civilizing force in a barbarous land [12]. Arturo Barea, one of these Spanish soldiers, did not see it that way: “‘Civilize the Moroccans . . . we?” he asked. “We from Castile, Andalusia, Gerona, who cannot read or write? Nonsense! Who is going to civilize us?” [13]. Barea called Spanish colonialism in Morocco part battlefield and part brothel, and echoed the frustrations of the average Spanish soldier. Even after army-wide raises in 1918 and 1920, most Spanish officers were so badly paid they had to take second jobs. Non-commissioned officers and conscripts got barely edible food, little if any medical treatment, and were notoriously underpaid and unhealthy. Most of the infantrymen in Morocco were completely untrained.

The Army was overloaded with officers, most of whom preferred garrison life in Spain to the mountains of the Rif. Corruption and incompetence made things worse. Promotions usually went to the most senior men, not the best or the most honest. In September 1922, during the height of the war in the Rif, officers in the Larache Sector of the Spanish Protectorate were caught embezzling over a million Spanish pesetas ($143,000) in money and supplies [14]. Privates and sergeants often traded their Mauser rifles and ammunition for fresh fruit and vegetables. Many of these guns ended up in the hands of Rif fighters.

“Berbers carrying captured rifles. A Spanish Mauser and a French Berthier Carbine.” Source: Wikipedia Commons.

The only effective fighting force defending the Spanish Protectorate was the new Spanish Foreign Legion. Nicknamed the Tercio, it was established in January 1920 as an imitation of the French. Just as the French legion was based in Algeria, the Tercio’s home was Morocco. The Tercio drew adventurers of all kinds, including Spaniards, exiled Russian noblemen, a few criminals, and at least one black American [15].

The soldiers of the Tercio were paid far more than regular soldiers and got substantial enlistment bonuses. Their esprit de corps was high (the Tercio went into battle shouting “Long Live Death”), and they fought 845 battles between 1920 and 1927 during the Rif War. One of their number, a middle class Galician, distinguished himself as a brave and fearless Tercio officer and became a general at the age of 33. His name was Francisco Franco.

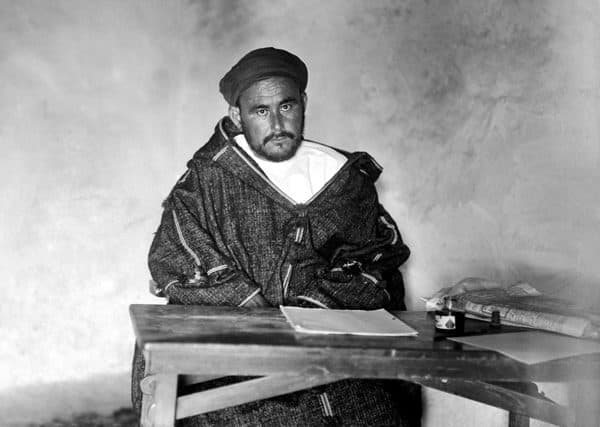

Not even the Tercio could save Spain from the major blunders of the early part of the war. By 1920, the Berber tribes were ready to revolt against both the French-backed sultan in the South and the Spanish soldiers guarding Ceuta and Melilla. The leader who unified the Berber tribesman was Abd el-Krim. Born in the village of Ajdir near Alhucemas Bay on the Mediterranean Sea, Abd el-Krim attended Spanish schools in Melilla as a boy and studied the Koran in the holy Moroccan city of Fez.[1] In 1906, he took his first job as the editor of the Arabic supplement to the Spanish-language newspaper, El Telegrama del Rif. The future insurgent and self-declared Amir (“prince”) of the Republic of the Rif began his path towards Rif nationalism while teaching Arabic to Spaniards in Melilla.

Abd el-Krim decided that the mineral wealth of the Rif ought to go to Berbers, not Spaniards. He also wanted a national state for the Rif Berbers, who, unlike their neighbors, had never been Arabized. This state would practice sharia law but would also hire European advisers to teach European medicine and science. By the summer of 1921, Abd el-Krim’s tribal army of the Rif had 3,000 to 6,000 men.

The two men in charge of the Spanish forces in the Rif were General Manuel Fernandez Silvestre and General Damaso Berenguer. Silvestre was a fight-first imperialist who, in 1921, was using the army to increase the size of the Spanish Protectorate. Berenguer had more limited ambitions: trying to get Madrid to do something about the sorry state of the Spanish Army. Silvestre and Berenguer were both born into military families in Spanish Cuba and both underestimated the Rifian threat.

Abd el-Krim – 1922. Credit: Album / Oronoz

In July 1921, Abd el-Krim’s Berber army laid siege to most if not all of the Spanish forts running the length of the protectorate. Many were miles away from water, and Spanish soldiers drank vinegar, cologne, ink, and the juice from peppers and from canned tomatoes [16]. The Spanish sent relief columns from the centrally-located fort at Annual, but the Berbers ambushed and massacred them. Berbers then seized Annual itself. Gen. Silvestre died in the fighting (some sources say he committed suicide), and thousands of Spanish soldiers were shot in the back or hacked to death by sword-wielding Berbers as they fled. By August 1921, thousands of Berber tribesmen and mujahidin were camped on the outskirts of Melilla. If they had had any experience in urban warfare, they might have overrun the city.

The bloodletting was atrocious. Berbers attacked the fort at Monte Arruit — not 30 miles south of Melilla — which held out for weeks. When the exhausted and starving Spanish surrendered, Berbers rushed in and stabbed every Spaniard to death. All told, the disasters of 1921 cost 13,192 Spanish lives and saw the loss of 20,000 Mauser rifles, 400 machine guns, and 129 cannons [17].

The defeat was so terrible that King Alfonso XIII backed a military coup by the Andalusian General Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1923. De Rivera blamed the mostly liberal civilian government for not spending enough money on the Army. He wanted to abandon Morocco, but found a military solution: abandon garrisons that could not easily be defended, let the Tercio do the hard fighting, and give recruits from Spain intensive training in the fortified cities of Ceuta and Melilla.

The africanista faction, which wanted Spain to stay and fight in Morocco to uphold Spanish prestige, opposed De Rivera’s policy of strategic retreat, but beginning in 1924, the Spanish abandoned the few forts that had not fallen to Abd el-Krim. Retreating Spanish soldiers found heaps of corpses that had not been buried since the disaster of 1921; corpses had been beheaded, disemboweled, sawn in half, eyes and genitals removed [18]. During the retreat, Rif Berbers captured the city of Chaouen (Al Aaroui) and parts of the protectorate. Thousands of Spanish soldiers died during the retreats, as Berber snipers fired on them from the high ground. On the last day alone, General Franco lost 500 of his legionarios.

Francisco Franco statue in Melilla. This statue was made before Franco became the Head of State and celebrates his achievements in the War of Africa. (Credit Image: © Artur Widak/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

That year — 1924 — was the high point of the rebellion. World opinion saw Abd el-Krim as an underdog fighting for freedom. The international city of Tangier, dominated by British and American businessmen, briefly let munitions and food through to Abd el-Krim. Would-be Islamic insurgents around the world took inspiration from the fight against Christendom.

Communists supported the rebels. The French Communist Party sent aid, while the Comintern in Moscow sent two agents. Jacques Doriot, who later founded the fascist French Popular Party, also sent aid [19]. Abd el-Krim played up his anti-imperial credentials by sending a letter to a convention of Latin American leftists comparing his war against Spain to their own wars of independence.

Yet, even in the midst of success, there was a threat to the south: the much more powerful French Morocco. Here were better-trained and better-equipped French soldiers, including the Foreign Legion, along with Senegalese and Arab units. The man in charge was General Louis Hubert Lyautey, France’s greatest colonial soldier.

Lyautey, who had fought in French Indochina, Algeria, and Madagascar, believed in letting the Berbers and Arabs run their own affairs. He also thought France had a duty to improve the lives of the locals, and his soldiers built hundreds of schools, hospitals, banks, and railroads. The problem was that the Rifians did not recognize the borders between the French and Spanish zones. The two sides began to clash in 1924.

Despite their advantages and their belief in their innate superiority to the Spanish Army, the French at first fared no better against the Berbers. By July 1925, the Rifians had overrun 43 of 66 French outposts in eastern Morocco and captured 51 cannons, 200 machine guns, 5,000 rifles, and 35 mortars [20]. Fighting together, French and Spanish forces finally began to turn the tide by attacking from the north. An amphibious landing on September 8, 1925 took the vital Mediterranean beachhead near the Rifian capital of Ajdir. Most of the 13,000 soldiers were Spanish, led by General Jose Sanjurjo, but with support from the French under General Philippe Petain.

Led by the Tercio, it took the Spanish troops weeks to clean out Rifian snipers and artillery from the many caves above the landing site. In the skies, the French Escadrille Cherifienne, which included American volunteer pilots, provided the invasion force with air cover and plenty of bombs. After a bloody victory and the destruction of Ajdir, the Republic of the Rif was as a good as dead.[2] Rather than surrender to the Spanish, who would have executed him, in 1926 Abd el-Krim surrendered to the French. He was exiled for more than 20 years to the French island of Reunion, where he lived comfortably, courtesy of the French.

The Rif War, which formally ended in mid-1927, is remembered today as one of the first awakenings of Moroccan nationalism. The modern kingdom and its people see Abd el-Krim as one of their founding fathers, even though Rifian Berbers despised Morocco’s traditional Arab ruling class. After independence from France and Spain in 1956, the Moroccan government asked Abd el-Krim — then living in Cairo — to return home. The old insurgent refused, noting that there were still French, Spanish, and American soldiers in Morocco.

The Rifian Berbers who came close to pushing out the Spanish, chafed under Moroccan rule. Upset that so few government positions went to Rifian natives, members of the Beni Urriaguel tribe founded the Popular Movement and the Rif Movement for Liberation and Liquidation in 1958 to seek independence. Ironically, one of their biggest complaints was the new government’s decision to replace the familiar Spanish language with French [21]. Fighting began in October 1958, but Moroccan troops and policemen put down the Berbers far more brutally than the French or Spanish ever did.

As for the Spanish today, they may occasionally enjoy a good period drama set during the Rif War, but they are more concerned about colonization by Moroccan “migrants.” In 2018, the ruling Socialist Party in Madrid let in more than 64,000. This human wave earned the Socialists a crushing defeat in Andalusia, where the upstart right-wing party Vox took off thanks to its anti-immigration stance. On April 28, 2019, Vox won 24 seats in the Spanish general election — a fine showing for a party’s first election. Vox and other patriotic movements in Spain will continue to rise thanks to increased immigration and the constant anarchy in Ceuta and Melilla, where sub-Saharan Africans continue to pour in and tax the Spanish migration system.

Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich in Morocco, a 1930 film about a cabaret singer and a Legionnaire who fall in love during the Rif War. Credit: PARAMOUNT PICTURES / Album

If Spaniards want to keep their identity and their illustrious history, which includes not only the victory in the Rif but the conquest of the New World, they must find the courage of their ancestors and defeat the new Moors trying to destroy the Spanish crown, the Spanish faith, and Spain itself.

* * *

[1]: Ian Rutledge, Enemy on the Euphrates: The Battle for Iraq, 1914-1921 (London: Saqi, 2015): 134-135

[2]: Rutledge, Enemy on the Euphrates, 293-311.

[3]: Rutledge, Enemy on the Euphrates, 177.

[4]: Sean McMeekin, The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908-1923 (New York: Penguin Books, 2015): xx.

[5]: Ibid.

[6]: John Harvey, With the French Foreign Legion in Syria: Fighting with the Legion of the Damned (London: Greenhill Books, 1995): 176-177.

[7]: Dario Fernandez-Morera, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain (Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books, 2016): 20.

[8]: Fernandez-Morera, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise, 38.

[9]: Fernandez-Morera, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise, 186.

[10]: David S. Woolman, Rebels in the Rif: Abd el-Krim and the Rif Rebellion (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1968): 3.

[11]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 9.

[12]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 57.

[13]: Ibid.

[14]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 108.

[15]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 68.

[16]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 90.

[17]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 96.

[18]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 103.

[19]: John Cooley, Baal, Christ, and Mohammed: Religion and Revolution in North Africa (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965): 191-193.

[20]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 182.

[21]: Woolman, Rebels in the Rif, 226.

[1] Mhamed el-Krim, the rebel leader’s brother, enjoyed an undergraduate education in Madrid courtesy of the Spanish government.

[2] The Escadrille Cherifienne was disbanded in 1925 after the bombing of Chaouen, which killed hundreds of civilians. The American government took the brunt of the criticism, despite the members of the squadron all being volunteers who were paid and employed by the French government.

- Post TagsColonialism, Featured, Islam in Africa, Racial Conflict