What Happened at the Colored Orphan Asylum?

- Post AuthorBy Jane Weir

- Post DateFri Jul 26 2019

This is the story of a vacant lot with a colorful and possibly cursed history.

There is a vacant lot at the corner of West 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, the only one for blocks around. It’s just dirt and rubble, surrounded by excavation fences covered with posters. The sidewalk is a popular venue for young urban blacks to do break-dancing (or something) for the edification of passing tourists. For a long time, a 76-story hotel-condo skyscraper has been scheduled for the site, but the project keeps running into snags.

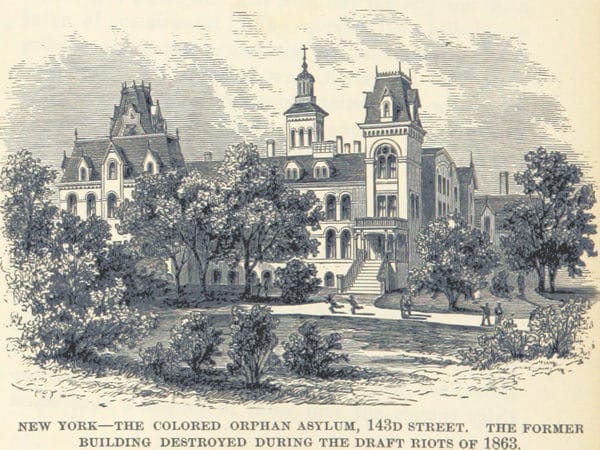

Now it’s just an eyesore, but it was occupied by a succession of townhouses and office buildings from about 1866 to 2012. Nearby, we have the New York Yacht Club, the Century Association, the Harvard Club, the Princeton Club, the Penn Club (formerly the Yale Club, till 1915 when that establishment moved to grander accommodations two blocks away). It’s a very posh location, but also a sort of landmark — the site of a watershed event in 19th century New York City history. Here was the Colored Orphan Asylum, which was famously destroyed on the night of July 13-14, 1863, during the so-called “New York Draft Riots.”

In historical pulp-fiction you will sometimes read that the orphanage was burned down with the colored orphans still inside, or that the blaze was started by an “Irish mob” of men who were angry about the new draft call-up, and for some reason decided to take it out on the poor black children. Like all the best propaganda, this is mostly hokum. Nobody was burned alive or died from the conflagration. It was a carefully organized, professional case of arson. The students and teachers were all ushered out by four p.m., the fire was set around six, and a little later an evening rainstorm came by to put out the fire.

Any New York “mob” in those days might well have been Irish, for the same reason a mob in Dublin would be: That’s what the populace largely was, a point readily grasped by anyone who skims through an early-1860s copy of Trow’s New York Directory. But if the anti-war “mob” had any leader, his name was John Urquhart Andrews, and he was a tall, bearded young lawyer originally from Portsmouth, Virginia. Andrews was eventually convicted of inciting civil unrest and sent up the river to Sing Sing. But my main point here is that the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum was neither a mob scene nor an isolated case of arson. All the wood-framed buildings in the vicinity along Fifth Avenue were torched: hotels, pubs, an ice cream parlor, even the buildings of the Allerton Stockyards — a big cattle pen and abattoir just a block up Fifth Avenue — incredible as that seems to us today. The orphan asylum itself was built of wood, brick, and stucco. After the fire and rain, its blackened walls stood for another year. Then the City pulled them down.

There are two theories about the arson. Newspapers (including the New York Evening Express and Ben Wood’s Daily News) speculated that it was part of a covert urban-renewal program. Most of the land in the neighborhood belonged to the city; today’s Midtown Manhattan was still mostly undeveloped north of 42nd Street until you reached the still-new, lush, Central Park at 59th Street. The City had been charging low or nominal rents for these properties, but now it wanted to develop the area into high-ticket properties.

That was the rumor going around, and that’s pretty much what happened. When charitable folks pitched to restore the blackened Colored Orphan Asylum — build it bigger and better! — the Common Council of New York said it wouldn’t renew the lease. City fathers had a certain vision for the city, and colored institutions with long-term low-rent leases didn’t figure in it. Along with other eleemosynary institutions (the insane hospital, the deaf-and-dumb institute, etc.) the asylum was moved far, far away — up to the northern wilds of Manhattan. Likewise, the Croton Cottage ice cream parlor didn’t return, nor the Allerton family’s slaughterhouse and stockyards, or the antiquated Bull’s Head hotel and tavern the Allertons owned on Fifth Avenue.

“Bull’s Head Hotel, depicted in 1830.” – Wikipedia

The real arsonists, the “really guilty parties . . . were the Fifth Avenue property interests . . . between Forty-fourth street and the Central Park,” said the Evening Express (October 31, 1863). This was in response to a speech by Republican candidate for state attorney general, who had blamed the destruction of the Colored Orphan Asylum on “the Irish.” Yes, that was the official Republican cover-story, said the Evening Express. However, those “property interests” could probably give “more cogent reasons for the destruction of Allerton’s cattle market and the Colored Orphan Asylum.”

Apparently these interests wielded a great deal of power with city government. This would explain why no firemen or policemen intervened to stop the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum or the other buildings. Fire companies stood by while structures burned. Most policemen stayed close to their precinct stations or at the downtown Metropolitan Police headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street.

There’s an alternative theory for the arson, less credible but more enticing: The hidden mastermind was actually Columbia College’s Professor of Mechanics and Physics, Richard Sears McCulloh. Columbia (not yet a university) had recently moved from a downtown campus near City Hall to a new spread in the East 40s, just a few blocks from the orphan asylum. McCulloh’s lab was therefore nearby, conveniently located for all arson and urban-clearance needs.

An avid chemist and inventor, McCulloh afterwards scarpered off to Richmond to develop secret weapons for the Confederacy. By the end of the war, he had perfected a lethal-gas bomb intended to break the Yankee encirclements of Richmond and Petersburg, but those cities fell before he had a chance to use it. McCulloh was caught and imprisoned, but ended his days as a professor at Washington and Lee. George Templeton Strong, the celebrated 19th century New York diarist, suspected that McCulloh was behind the arson on Fifth Avenue.

Maybe both theories are correct. New York City wanted to upgrade its Midtown properties, and Columbia’s senior scientist gave a helpful hand with his deep knowledge of incendiaries. But if you depend upon misinformed popular accounts of the “Draft Riots” — and don’t read 1860s newspapers or George Templeton Strong — you won’t get a hint of any of this.

For over a century-and-a-half the tale of the Colored Orphan Asylum has been the centerpiece of the “Draft Riots” legend, a grand fable that itself is a kind a great-granddaddy of contemporary anti-white propaganda. After the black riots of the 1960s there was a rash of poorly researched, somewhat fictionalized books about the “Draft Riots,” trying to demonstrate that urban rioting had been a white thing, too — poor whites, immigrant whites! Never mind that they weren’t all poor, and most weren’t immigrants; facts shouldn’t get in the way.

Anti-black bigotry is always a big theme in these narratives. For example, I have a historical novel called The Draft Riots, July 1863, by one Irving Werstein (Simon & Schuster, 1971). Werstein just can’t leave the N-word alone. A “mob” of “rioters” climb over the fence of the Colored Orphan Asylum, and trample the flower bed and vegetable patch.

“We’re here to clean out your ni**er nest,” a pock-faced man bawled.

“Let us get our hands on the little ni**ers,” a woman cried.

“Stop all this damned talk and burn the place down,” a drunk yelled.

Subtle stuff! Whiskey gets passed around, a whore gets knifed. Someone sets fire to some curtains, and that’s the end of the orphan asylum.

Slightly more historically-minded is a book by James McCague called The Second Rebellion: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 (Dial Press, 1968). This is supposed to be nonfiction but take that with a grain of salt. McCague bases his social backdrop on Herbert Asbury’s lurid, mostly fictional, Gangs of New York (1927), in which nearly everybody lives and riots in the Five Points district, a downtown slum that actually had its heyday around the War of 1812. In 1863, the main residential areas and most of the action under review here were close to Midtown. McCague has some other odd ideas. He thinks the Colored Orphan Asylum was on the lot currently occupied by the New York Public Library: well, he’s off by only two blocks. He retails a completely uncorroborated, unsourced story that there was one little colored girl in the orphan asylum who didn’t survive. She hid under her bed, then “the mob” found her and beat her. She had no name, apparently, and doesn’t appear on any list of the deceased.

There are many confused, sensationalist tales about “The Bloody Week!” (as a July 1863 pamphlet was titled). Most of the stories originate in the shoddy, lurid journalism of the time. If you spend a lot of time with newspapers from the period, you get the idea that reporters were all staying indoors and making it up. The abolitionist, radical-Republican New York Times (July 14, 1863) could not get basic facts straight in its coverage of the Colored Orphan Asylum, saying it housed “an average 600 or 800 homeless colored orphans.” The agreed-upon number today is about 230. And they weren’t homeless, and most had at least one parent. Despite its name, it was more of a fee-paying boarding school than a home for foundlings. Further on, notes the Times: “There is now scarcely one brick left upon another of the Orphan Asylum.” Obviously, the Times newsie didn’t stop by the place, or he’d have known the walls were still standing.

Who hasn’t read that “dozens” or “hundreds” (“thousands”?) of black people were lynched by angry mobs that week during the “Draft Riots”? Actually, there were only about a half-dozen, and nearly all were blacks with pistols, taking pot-shots at white people on the street. In the newspapers, these stories follow a similar pattern. Here is a classic Greenwich Village misadventure, taken from wire-service stories (from the NY World and the Daily News) printed by the Philadelphia Press on July 15, 1863:

An intense excitement was created in the vicinity of Bleecker Street and Sixth avenue [sic] last evening, in consequence of a white citizen being shot while passing up Bleecker Street. The facts as ascertained during the excitement are as follows: A gentleman, whose name has not been thus far ascertained, was going to his home, when he was accosted by a partially intoxicated negro, who was so abusive in his language as to provoke a quarrel. Some altercation ensued from this abuse, when the negro drew a pistol and shot the white man, who soon after died.

The story then segues into a similar one on a nearby street, in which there are four blacks, and a white man in a crowd gets shot three times and dies instantly. Then, a hanging; and someone starts a fire under the body. Did these lynchings actually happen like that? I don’t know, but the scenario is far different from gratuitous, unprovoked murder.

The two events (if in fact they are two different events) both happened on Monday, July 13, while the Colored Orphan Asylum was burning two miles to the north. Earlier that day, on Spring Street, another black man had an altercation with a white man and shot him in the groin, “from which it is feared he cannot recover.” (NY Herald, July 14). These are all typical of news items that week, except that, as in the last instance, the triggermen weren’t always caught and killed.

At the end of that week, most of the people known to have suffered a violent death (about a hundred) were white. Most of them were not shot by blacks. At least half were shot by Federal troops called in after the first couple days to put down the “riot.” Some of the deceased were cops, some were soldiers themselves, some fell out of windows; while a few were civilian victims of our black pot-shotters. (A named listing of the dead, wounded, and arrested appears in Adrian Cook’s The Armies of the Streets, University Press of Kentucky, 1974.)

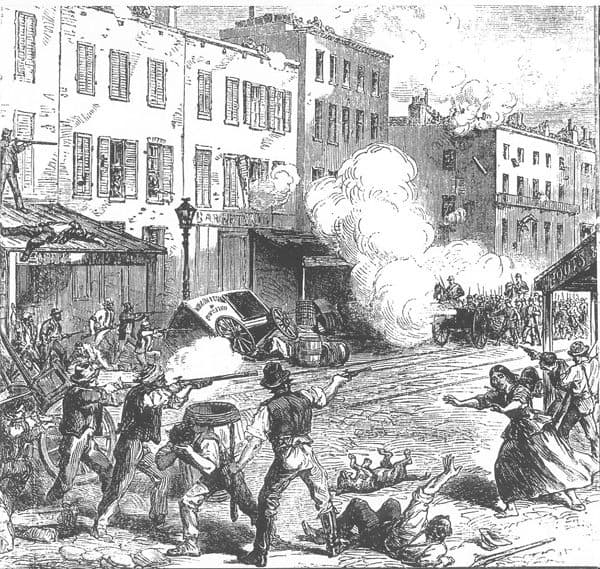

“A drawing from a British newspaper showing armed rioters clashing with Union Army soldiers in New York City.” – Wikipedia

The most grotesque tales of the period are urban legends that went viral at the time and are past belief. They are told by people who could not possibly have been on the scene. Another book I have, Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored Men, Held in the City of Syracuse, N.Y., October 4, 5, 6, and 7, 1864, offers the following tidbit, related by the lushly sideburned Negro divine, Henry Highland Garnet of New York City, who has just been introduced by Mr. Frederick Douglass of Rochester, N.Y.:

Mr. Garnet drew a picture of the shadows which fell upon New-York city [sic] in July 1863, where demoniac hate culminated in that memorable mob. He told us how one man was hung upon a tree and that then a demon in human form, taking a sharp knife, cut out pieces of the quivering flesh, and offered it to the greedy, blood-thirsty mob, saying “Who wants some ni**er meat?” and then the reply, “I!” “I!” “I!” as if they were scrambling for pieces of gold.

Is there a moral to all this? There is, but it’s more of a backstory. The “Draft Riots” fable, and misapprehensions about the Colored Orphan Asylum, are usually presented as though they came out of nowhere. Or, at best, they are explained with a lame, tendentious pretext, such as “poor whites angry about being drafted (particularly to fight in a war to free black slaves).” Those excuses are evasions, beside the point.

By 1863, urban race riots had been a frequent occurrence for at least a year, primarily in the Midwest. So far, New York had blessedly escaped the problem. But the founder/publisher of The New York Herald saw troubles ahead, and described the cause in a succinct 1862 editorial:

Much indignation has been shed by some of the abolition papers about the negro riots; but these very journals, and the leaders of the faction of which they are the organs, are the real cause of the disturbances. They have so filled the empty heads of the blacks with silly notions of equality that many of them have become exceedingly insolent to white men and women in the streets, on ferry boats, in cars and other places. They are known frequently to push white women off the sidewalks and to insult them. Then a point has been made of late by some capitalists and manufacturers to turn out of their establishments white men and women by hundreds and fill their places with blacks. These things have led to collisions, and the agitators who puff Sambo up with absurd ideas of his importance are to blame for what has occurred. The Irish, as a class, are industrious, hard-working, quiet and loyal to the government. The riots are fomented and brought about by the abolitionists whose philanthropy is ever sure to redound to the injury of the unfortunate negro, who, if left alone by the anti-slavery agitators, would conduct himself properly and never provoke the hostility that is being awakened against him.

— James Gordon Bennett, TheNew York Herald, August 7, 1862

Of course, there was much more to the so-called “Draft Riots” in July 1863 than City-sanctioned arson on Fifth Avenue, or trigger-happy blacks. There were also very serious, organized assaults on gun factories and an armory; and for two or three days there were barricades and armed rebellion in some neighborhoods. But the key words here are “very serious” and “organized.” In New York there was a strong body of “Peace Party” Democrats, including many journalists, intellectuals, clerics, and politicians. They held conventions at Cooper Union, and constantly wrote and protested against the war and the war profiteers. They were a mortal threat to the abolitionist Republicans. So the abolitionist papers pushed a story that the New York Democrats had incited a “Copperhead riot” led by a “drunken Irish mob.” It made a good story, and many of their readers wouldn’t know any better.

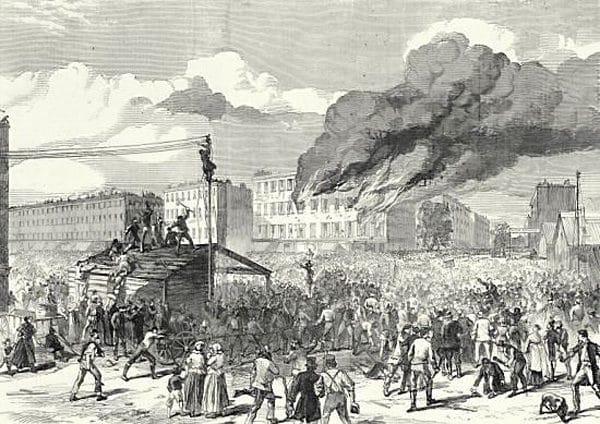

The Riots In New York: The Mob Burning The Provost Marshal’s Office, 8 August, 1863. (Credit Image: © Album via ZUMA Press)

It’s also undoubtedly true that when the police removed themselves from the streets and hid out in their precinct stations, there was a fair amount of street-crime and looting. One young hooligan even got sentenced to 10 years for stealing a hat (one of the few convicted of anything). But this had nothing to do with political protests or rebellion.

Over a century-and-a-half later, you can find lots of photographs of New York in that summer of 1863. New York probably had the greatest concentration of professional and amateur photographers in the world. You can find stereoviews and dry-plate prints of picnics and concerts in Central Park; swans swimming in the lake, shoppers and horsecars on Broadway; or even the famous midget, General Tom Thumb, with his midget bride. What you won’t find is photos of rioting mobs, or the Colored Orphan Asylum being torched by rioters, or dozens of innocent negroes being lynched.

How could such excellent photo opportunities be missed? Perhaps they didn’t happen, or no one knew about them at the time.

- Post TagsAmerican History, Featured, Liberal Myths, Racial Conflict