Madison Grant, The Conquest of a Continent, or the Expansion of Races in America, Liberty Bell Publications reprint, 2004 (originally published, 1933), 393 pp.

The Conquest of a Continent by Madison Grant is considered one of the classics of American racial-nationalist thinking. Grant, an accomplished amateur naturalist and eugenicist, devoted much of his life to promoting the ideal of a self-consciously white America. This book, written in 1933, is a history of the European conquest of North America, with a particular concentration on the racial origins of the founding stock. Grant’s historical writing is generally sound and illuminating. His Nordicism led him to positions likely to strike today’s readers as eccentric and misguided, but he had a deep understanding of the importance of race.

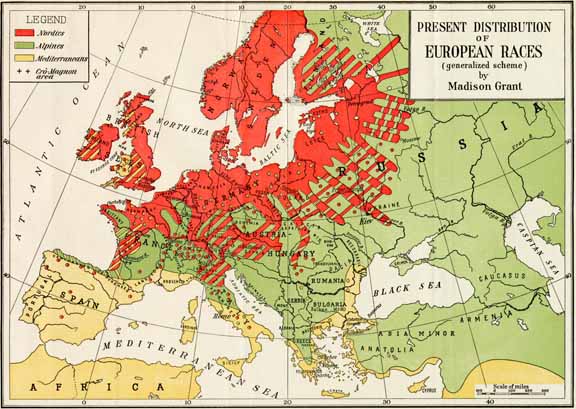

From Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race.

Henry Fairfield Osborne, a noted paleontologist and racial activist, strikes the book’s keynote in the introduction: “The character of a country depends upon the racial character of the men and women who dominate it.” Writing at a time when it was not wildly controversial to say so, he went on to add that “moral, intellectual, and spiritual traits are just as distinctive and characteristic of different races as are head-form, hair and eye color, physical stature and other data of anthropologists.”

Grant found significant differences among what were then accepted as the major sub-races of whites: Nordics, Alpines, and Mediterraneans. He was so concerned about the undesirable qualities of certain whites that The Conquest of a Continent spends more time thumping Alpines and Catholics than blacks. Grant seems to have thought his fellow Nordics needed no warnings against blacks; they were mostly confined to the South, where they were under firm control. The real danger was Southern and Eastern Europeans slipping into the country.

Grant explains that he wrote the book as a result of the Immigration Act of 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act), which set national quotas for immigration. The quotas were based on the ethnic/national mix of 1890, and he was incensed by the maneuverings of Catholics and non-Nordics to inflate their portion of the population in the hope of raising their immigration quotas. The Irish, in particular, he found to be “perhaps the most industrious in this occupation.” He hoped to set the record straight by explaining where settlers came from and what each group contributed.

Alpines getting above themselves.

In an earlier volume published in 1916, The Passing of the Great Race, Grant describes the virtues of what he considered to be his own sub-group: “The Nordics are, all over the world, a race of soldiers, sailors, adventurers and explorers, but above all, of rulers, organizers and aristocrats, in sharp contrast to the essentially peasant and democratic character of the Alpines.” He writes that most of what is good or distinguished in world history was the work of Nordics. He claims that the rulers of ancient Egypt and the Aryan invaders of India were Nordic, and that most of the great men of the Italian Renaissance were blond Nordics.

Alpines, on the other hand, are a sorry lot: “always and everywhere a race of peasants, an agricultural and never a maritime race.” “This race is essentially of the soil and in towns the type is mediocre and bourgeois.” In Conquest he adds that although Nordics are nomadic, Alpines “stick close to the land and breed persistently.” Osborne, in his introduction is far less harsh, writing of “the great achievements of the Alpine race in engineering, in mathematics, and in astronomy.”

Grant believed that the Mediterraneans were more closely related to Nordics than Alpines, and are a respectable lot: “[W]hile inferior in bodily stamina to both the Nordic and the Alpine, [the Mediterranean] is probably the superior of both, certainly of the Alpines, in intellectual attainments. In the field of art its superiority to both the other European races is unquestioned although in literature and in scientific research and discovery the Nordics far excel it.”

Grant did not carefully define the homelands of the Mediterraneans, but some of them were originally from the Middle East and North Africa. They were Europeans, however, and though shorter and darker than Nordics, they do not resemble the people who now live in those ancestral areas.

Grant is precise, however, about Alpines. They run from the center of France, through north Italy, South Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Balkans, Russia, Asia Minor and into Asia itself. He believed long-headed Nordics and Mediterraneans could be unfailingly distinguished from Alpines by skull shape. Alpines are round-headed, like Asians, and Grant believed they got that way from intermixture: “The East European Alpines are saturated everywhere with Mongol blood . . . .” The Mongol, he notes, is just as smart as the Nordic, but does not have his heroic traits. Although Grant took the traditional view that miscegenation, especially of distant races, brings out the worst traits of each, he ventured the view that crosses between Nordics and Mediterraneans may be the one desirable exception.

Although Nordics may be inherent rulers, Grant worried that they often failed to keep Alpines in check. Both the French and Russian revolutions, he writes, were Alpine revolts against Nordic nobility. Grant has such a low view of Alpines that he even writes: “This steady increase of round-skull Alpines everywhere in Central Europe in recent centuries is one of the most ominous racial facts that confront us.” Today, it would be hard to imagine any racial activist fulminating against the threat of the Austrians and the Swiss!

Who Founded America?

Fess Parker, playing a representative of hardy, useful stock.

Grant is on firmer ground when he describes the peopling of the continent. In addition to carefully tracing the geographic and racial origins of settlers, he always comments on the desirability of the “stock,” noting who was rich or poor, noble or common. In his view, wealth and cultivation are always signs of better stock.

Grant is therefore disappointed to note that the settlers of New England were of no better than yeoman class — but they were Nordics, and “the general level was sound and intelligent.” He is happier with the blue-bloods who came to Virginia after Cromwell executed Charles I in 1649.

Given this interest in social class, he is surprisingly unworried about the criminals who were transported to the colonies in the early days. He notes that an Englishman could be deported for minor crimes that did not denote hopeless inferiority, and that many “criminals” were simply men on the losing side of British civil wars. Captives of the 1685 Battle of Sedgemoor — the last battle on British territory — were “able-bodied and intelligent men,” and mostly Nordics. As for real criminal degenerates, he says there were “only a few thousand in all.”

Grant considered the circumstances of early immigration ideal for culling the herd. Only the enterprising set out, and only the hardy survived. Grant writes almost happily of the large numbers who died of disease and privation. He also likes the rebellious, freebooting quality of early settlers. “In contrast to England and Canada, we are an essentially lawless people,” he writes, pointing to Shay’s Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion, and the North Carolina “Regulators.”

Contributing to this independent nature were the Ulster Scots, who began to arrive in large numbers after 1720. Grant stresses that these were not Catholics but transplanted Scots, and he admires their pioneering, Indian-fighting spirit. As yet more rebels and dissenters arrived, they headed further west, opening the country. Grant largely dismisses any but English-speaking pioneers. He writes, for example, that “in Indiana, a typical American owes nothing worth mentioning to the original French population.”

He makes an exception for the Huguenots, for whom he has high praise. He describes them as racially indistinguishable from British Nordics, and estimates there may have been as many as 250,000. France, he argues, suffered greatly by expelling them.

Grant describes the colonies of 1776 as probably the most overwhelmingly Nordic and Protestant place on earth. The Revolution itself he calls a “costly and unfortunate internecine war.” He also deeply regrets the expulsion of the loyalists, who were in his view a high-bred, accomplished group: “some of the best Nordic blood in the country.” For him, their loss was as serious a genetic blow as the loss of the Huguenots was to France. He notes that many of the 80 to 100 thousand who left went to Ontario, where they organized fierce resistance to American annexation during the war of 1812.

Of the limited immigration that preceded the War Between the States, he particularly approves of the Scandinavians — “hardy Nordics” — and of the Germans who came after the failed revolutions of 1848. They were “Nordics, including individuals of some culture and distinction.” As for the “self-styled Spanish-American” who arrived as a consequence of the Mexican-American War, “the Spanish part of the description must be considered largely a courtesy title” since the population was mostly Indian. Numbers were very small, however, with the result that “our population and our institutions remained overwhelmingly Anglo-Saxon down to the time of the Civil War,” and “in 1860 the United States was at its high-water mark of national unity.”

High tide for Nordic America.

The war itself he sees as a racial catastrophe. The 600,000 men who died would have, along with their descendants, filled up the West and made unnecessary “the immigrants we recklessly invited to our shores.” Immigration of non-Nordics from 1860 to 1930 was a disaster that met the “unfilled demand for low-grade factory labor in the East.”

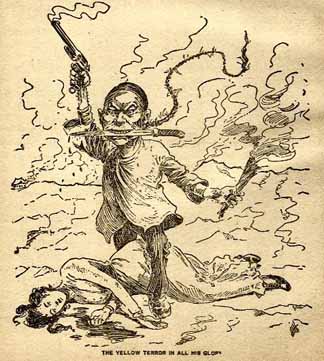

When the people, rather than their rulers, had a chance to speak, their instincts were healthy. Grant recounts with satisfaction an 1879 California ballot to limit Chinese immigration, in which the vote was 154,638 to 833. “There have been few issues in American history carried by a more nearly unanimous vote,” he adds.

Fortunately, the country recognized the evils of non-Nordic immigration and passed the 1924 quotas. For Grant, this act of racial preservation was the equivalent of a second Declaration of Independence. He was worried, however, because the quotas applied only to Europe, and thus did not keep out Mexicans, West Indians, or even Filipinos. One happy side effect of the Great Depression, he noted, was that it stopped the flow of undesirables.

At the time Grant wrote, the US had a population of some 109 million, of whom he estimated 80 percent were Protestant and 70 percent Nordic. “On the whole it is the northern and central parts of the Atlantic Coast that have become the worst un-American parts of the Union,” he writes, but he was glad to note that “the Southern States are still almost wholly native white.”

Grant assumed immigration depressed the native birthrate, and wondered whether the British founding stock might not have had 100 million descendants had it been left to breed in peace. Always the environmentalist — he played a key role in saving the bison from extinction and in setting aside great tracts of wilderness — he warned that the population should not be allowed to exceed 150 million. He would have been appalled by the current mish-mash that is well over twice that figure.

Whites, good and bad

Grant wrote in harsh generalities and was not always kind to his favorites, the Nordics. “The most shiftless and least intelligent of them tended to collect in the less valuable lands at the fringes of civilization” and degenerate into “poor white trash.” He calls these depraved Nordics “a striking example to the eugenicist of the results of isolation and undesirable selection.”

Grant wanted the Chinese out.

In numerical terms, Grant considers the Germans the only significant non-British founding stock, noting that they numbered 250,000 at the time of the Revolution and were nine percent of the population by 1790. He concedes that they were “peaceful and industrious,” but does not like any group that clings to its language. He criticizes William Penn for welcoming what came to be known as the Pennsylvania “Dutch” — Palatinate Germans “largely of the round-headed Alpine stock.” He quotes Benjamin Franklin on the Germans: “Those who come hither are generally the most stupid of their own nation . . . ,” but agrees with Franklin that “their industry and frugality are exemplary.” He writes that Franklin had accurately predicted Germans would assimilate if not allowed to clump too tightly. The Amish and Dunkards, on the other hand, were exactly the kind of inward-looking groups Franklin warned a bout: In Grant’s view, they are “impossible to Americanize.”

Grant was an Anglophile, and shared the common British view of the Irish. He concedes that they are “predominantly Nordic,” but cannot forgive them for being Catholic. Any dissent from Protestantism fractures national unity, and parochial schools fuel disunity. He says the Irish should have been kept out of local politics, “for which they showed great aptitude.” He insists that until the potato famine of the 1840s, so-called Irish immigrants were Ulster Scots: neither Irish nor Catholic. It was only after the famine that America suffered from “the arrival of large numbers of ignorant and destitute South Irish Catholics.” He says Americans would have a uniformly high opinion of Britain were it not for Irish “agitators.”

As for Italian immigrants, the trouble was that “there was no discrimination as to type or quality.” “Many criminals were rounded up,” he writes, “especially in southern Italy and Sicily . . . . ” Southern Italians were “of extremely inferior type,” though the northern Italians who settled San Francisco were respectable. He quotes one observer of South Italians: “Dirty, lazy, weak, good-for-nothing idlers that they are.”

The marquis was “unsound” on race.

Grant was not keen on Jews either. He prefers German to Polish Jews, but both types are Alpines. “All these Jews are in sharp contrast to the Sephardim Jews, a superior group, largely Mediterranean in race,” he adds. He also had the idea that Galveston, Texas was dominated by Jews.

Grant disliked the French, and argues that whatever foolish sympathy Americans have for them is because of the romantic personality of Lafayette. The marquis, on the other hand, was unsound on race: an admirer of the Haitian Toussaint l’Ouverture, and head of the Société des Amis des Noirs. French Canadians are even worse than the French: “a fecund population of low cultural status,” and “a stocky, short-necked people, rather of the Alpine build, with eyes often rather dark.” He calls them “the most highly inbred of any of the large groups of the New World.” He says they would not fight against the Kaiser, so “their conduct during the World War was contemptible.”

As for American Indians, Grant is appalled by their cruelty, especially the torture of captives, and says this led them to be “regarded as ravening wolves or worse and deprived of all sympathy, while the Whites stole their lands and killed their game.” On the other hand, Grant is glad the continent was not empty when whites arrived because hostile Indians kept the frontier from advancing too rapidly. If pioneers had immediately scattered throughout the continent, they might have set up separate nations rather than a unitary state.

Grant is thankful that half-breeds were always considered Indian and not white: “This attitude toward the lower race has always characterized our American frontier and while very unpopular with the natives, has served to keep the White race unmixed, in sharp contrast to the French and Spanish colonies.”

Grant thought blacks were the worst threat to racial integrity, and argues that the entire population could have been deported for a fraction of the cost of the Civil War. Birth control “should be made universally available to the Blacks,” and all states should pass anti-miscegenation laws. He writes that miscegenation has generally been the result of crosses with “the lowest and most unintelligent type of white servant.” “Those admirers of the Mulatto who boast that he carries in his veins the blue blood of the aristocratic families of the South,” he adds, “would do well to read the actual records . . . .”

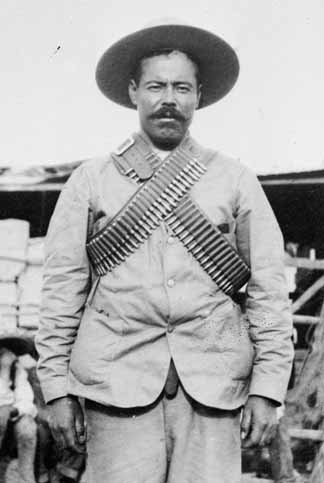

Pancho Villa: “no more than a homeopathic dose of European blood.”

The Conquest of a Continent touches briefly on Canada and Latin America. Grant writes that Canada is becoming non-Nordic even more rapidly than the United States but is blessed with a “negligible proportion of Negroes.” The entire landmass south of the Rio Grande is suspect because the claim to be white “by no means guarantees anything more than a homeopathic dose of European blood.” Thus, for example, in Venezuela, “it is doubtful whether one resident in fifty can properly be called a white man, except by courtesy.” In Panama, “North American influence has transformed it economically, but cannot change mongrels into a sound and vigorous stock.”

Grant was already worried about Mexican efforts to reconquer the Southwest. Of Mexicans in California, he writes, “there is a considerable hybrid element which does most of the talking, and a negligible element that can be considered white in the strict sense of the term.”

This leads to Grant’s highest priority policy recommendation: to extend the limitations of the 1924 quota act to the Western Hemisphere and to “suspend all naturalization for a generation at least.” He also wanted universal registration of the population so as to control illegal immigration.

At the same time, he wanted to hive off all non-white territories. Puerto Rico should be made independent “to give the United States protection from its own folly.” We should also “give the Filipino his independence, commend him to the benevolence of Providence and League of Nations, and have nothing more to do with him.” Domestically, Grant wanted to solve the black and Alpine problem by “regulat[ing] births by depriving the unfit of the opportunity of leaving behind posterity of their own debased type.”

Grant was ahead of his time in opposing any attempt to spread “American” values. He writes that non-whites have their own ways of doing things, “which for them may be, and in many cases probably are, as good as our own.” In another prescient observation, he pointed out the importance of solidarity with the whites of Southern Africa.

Hedging and Trimming

Grant generally believed that Nordics should stick up for themselves without apology, but even he does a little trimming. For example, he writes that the best policy would be to cut off all immigration because admitting only whites would upset Asians. Why worry about what Asians might think?

The 1930s were a completely different time from our own. This was the heyday of Jim Crow and immigration restriction; Nazi Germany had not yet discredited eugenics. Moreover, Conquest of a Continent was not self-published; it was issued by a top-tier commercial house, Charles Scribner’s Sons. And yet, Grant could not write with complete freedom. He sensed powerful forces mobilizing to shut down his point of view: “Our alien elements are to this day extremely sensitive to the public discussion of any of these matters. In this respect, Americans probably have less freedom of speech and freedom of press than exist in any of the countries of Europe.”

Indeed, the Anti-Defamation League set out to prove him right. Its director, Richard E. Gutstadt, wrote to editors of Jewish periodicals, “We are interested in stifling the sale of this book,” and urged them to kill it with silence. The league added that this would “sound the warning to other publishing houses against engaging in this type of venture.” Today, a host of organizations would rise up against “this type of venture.”

Needless to say, Grants efforts came to naught; the country moved sharply in the wrong direction, and the “second Declaration of Independence” was good for only 40 years. Grant would have been disgusted by today’s America but probably not astonished. Even in his time he had noted “a curious sentimental quality of the Anglo-Saxon mind, the effect of which is almost suicidal.” Had he been able to see the future, he might have been tempted to remove the word “almost.”

[Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in the December 2011 issue of American Renaissance.]