Judas and the Black Messiah: Pitch Perfect Propaganda

- Post AuthorBy Robert Hampton

- Post DateMon Mar 08 2021

In 1969, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover said, “The Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to internal security of the country.” Today, popular media see the Black Panthers as heroes who fought “white supremacy.”

The latest example of this is the film Judas and the Black Messiah. It’s about the Black Panther leader Fred Hampton and his relationship with federal informant William O’Neal. Hoover and the FBI considered Hampton a possible “black messiah” — a charismatic leader capable of uniting black militants and the (mostly white) New Left. The “Judas” is O’Neal, a common criminal recruited by the FBI’s COINTELPRO program to infiltrate the Black Panther Party of Chicago. The information O’Neal passed on to government agents allegedly led to Hampton’s death at the hands of law enforcement in 1969.

The film begins with footage of 1968’s race riots before switching to a speech delivered by Hoover (played by Martin Sheen) to an auditorium filled with FBI agents. He makes his famous claim that the Black Panthers are America’s primary threat and says the agency must prevent the rise of a black messiah. He shows a clip of Fred Hampton to his audience, warning them this man could be that figure. Sitting in the auditorium is Agent Roy Mitchell (played by Jesse Plemons), who dutifully notes Hoover’s directive.

Mitchell meets William O’Neal (played by Lakeith Stanfield) after O’Neal’s arrest for impersonating an FBI agent to try to steal a gangster’s car. Mitchell tells the black criminal that he can either take a lengthy prison sentence or start working with COINTELPRO. The program infiltrated several groups Hoover thought were domestic threats, from the Ku Klux Klan to the Communist Party, and in the late ’60s, the Panthers became the program’s major focus.

Jesse Plemons and Lakeith Stanfield in Judas and the Black Messiah (Credit Image: © Macro / Album / Entertainment Pictures via ZUMA Press)

Fred Hampton’s first scene in the film is at a local college giving a speech, in which he criticizes blacks who wear dashikis but don’t challenge capitalism. He claims to a skeptical audience that capitalists let blacks indulge in Afro identity because it poses no threat. He urges his black audience to overthrow capitalism and take power for themselves.

O’Neal joins the Black Panthers, but he isn’t enthusiastic. He’s frightened by the Panthers’ vast arsenal and shows little interest in political indoctrination. During a lecture on politics, Hampton makes O’Neal do pushups in front of the class for making a pass at a female classmate. Hampton tells the informant he must respect Panther women because they are our “sisters in arms.” The film tries to show the Panthers as feminists who always respected women, but that wasn’t the case. Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver bragged about raping white women as an insurrectionary act in his bestseller Soul on Ice. (Cleaver served time in jail for rape and admitted he raped both white and black women.) Panther leadership was allegedly responsible for murdering Betty Van Patter, a white bookkeeper who worked for the party. The party also opposed birth control, and “punished rank-and-file females for even minor ‘infractions’ by turning them out as prostitutes.” The film doesn’t mention any of this.

O’Neal realizes he isn’t getting close to Hampton, so he convinces Mitchell, his handler, to give him a car. The car elevates O’Neal’s status, and he becomes Hampton’s trusted driver. O’Neal, still working as an informant, begins traveling around Chicago with Hampton as he tries to build an anti-police “Rainbow Coalition” of common criminals, gang members, and down-and-out whites.

This worries the authorities and Hoover personally orders (in the film, at least) the arrest of Hampton on any charge possible. Police arrest Hampton for stealing $71 worth of ice cream and a judge sentences him to 2-5 years in jail. This is supposed to be an example of the system’s cruelty towards the Black Panthers. but the movie leaves out the details. According to court testimony, Hampton assaulted and held down the vendor while his friends stole the ice cream. Nor does the film mention that in 1969, Hampton was involved in kidnapping and severely beating a black couple over a missing gun scope. Hampton and 15 others were indicted.

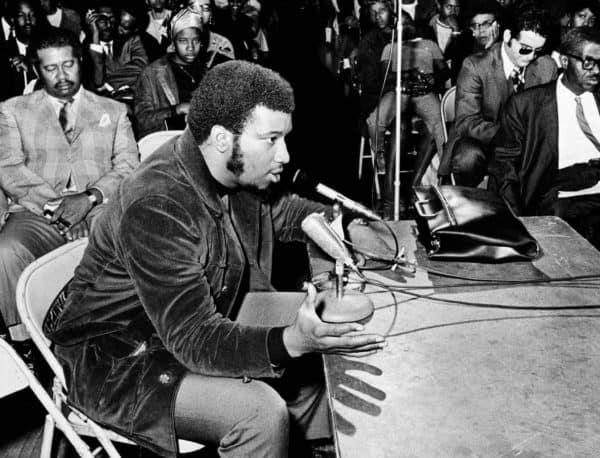

Fred Hampton (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

The film repeatedly plays loose with the facts, often changing details to make the Panthers look more noble and less violent. In the movie, the Panthers’ Chicago chapter takes in George Sams, a member of the New Haven chapter who is on the run. Sams proudly tells how his chapter tortured a suspected informant, Alex Rackley, with boiling water to get him to confess, and later killed him. The story terrifies O’Neal, who shares it with Mitchell and asks for reassurance that his status as an informant is as a secret as possible. Mitchell speaks with his superiors about this. They tell him that Sams is an informant and they know all about him. They laugh about Rackely’s murder and claim that an informant would never be involved in such a crime.

In reality, the New Haven Black Panthers murdered Alex Rackley after torturing him for three days. They claimed falsely he was an informer, but he did provide state’s evidence at the Rackley murder trial in exchange for a lighter sentence. Sams also implicated Black Panther leader Bobby Seale in the murder (though Seale beat the charge in court). The film claims Sams accused Mr. Seale at the behest of the FBI, but again, there’s no evidence for this. Sams’ role in the film is to imply that informants and provocateurs, not genuine Panthers, were the cruel and violent ones.

In another scene, a party member based on real-life Panther Larry Robertson pulls a gun on white cops who are harassing innocent blacks and a shoutout ensues. In both the real shoutout and the film version, police wound Roberson and he’s sent to a hospital. In the film, the police then murder him there but there is no evidence that happened.

Later in the film, police start a firefight with another Panther, Jake Winters (played by Algee Smith). Winters kills two cops before he’s gunned down. One of the cops pleads for his life as he lies wounded. Winters executes him. The movie Winters’ actions seem foolish but understandable. His anger is righteous and the police are brutal servants of an evil system. Jake Winters was a real Panther who killed two cops, one at point-blank range. However, police did not start the violence; Winters and another Black Panther ambushed them. In the film, Winters takes on the police by himself with just one gun. In reality, he and his comrade had a “substantial quantity of weapons.” They killed two officers, wounded six, and destroyed two police cars.

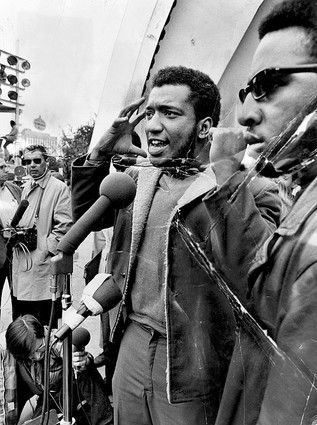

Fred Hampton, of the Illinois Black Panthers, speaks at a rally at Chicago’s Grant Park in September 1969. (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

The film also takes liberties with a shootout at the Panthers’ Chicago headquarters. The movie shows white cops harassing black passersby and baiting the Panthers into violence with racial insults. Cops also fire the first shots, claiming they saw a sniper on the roof, and the shootout is in the middle of the day. Police torch the headquarters afterwards. The actual shootout was after midnight and started when Panthers fired on passing patrol officers.

The informant O’Neal develops a close relationship with Agent Mitchell. The criminal sees the agent as a mentor who pays him well and takes him to fancy restaurants. Mitchell says he supports civil rights and touts his work against the Ku Klux Klan. But the white agent says he opposes the Black Panthers for “cheating their way” to equality and wanting to overthrow the system. He tells O’Neal the Panthers and the Klan are two sides of the same coin. To Mitchell, they’re both violent extremists who want to tear down this great country.

The film thus portrays Mitchell sympathetically, but J. Edgar Hoover is a zealous white supremacist who will do whatever it takes to destroy the Panthers. In one scene, Hoover asks Mitchell what he will do when his daughter “brings home a Negro.” Mitchell replies that his daughter is only an infant, but Hoover insists on an answer. Mitchell, clearly uncomfortable with the question, stammers that she won’t bring home a black man before demanding to know the point of the question. Hoover answers that this is a fundamental question because the young agent will have to worry about this if Hampton wins. The FBI director says the future of the white race depends on defeating the Black Panthers. There is no evidence that Hoover held such views or that this conversation ever took place.

The movie also claims Hoover ordered Hampton killed, but there is no evidence for this.

J. Edgar Hoover

On December 4, 1969, police killed Hampton during a raid on his apartment. The officers had a warrant to search for illegal weapons, and claimed the occupants fired first. In the film, it’s a gangland massacre; only police fire their weapons. They kill one Panther and wound several others before demanding to know where Hampton is. Once they find him, two officers shoot him at point-blank range and declare him dead.

Details about that raid are still murky. The officers’ initial story didn’t hold up, and charges against the surviving Panthers for attempted murder were thrown out. Chicago later paid the survivors nearly $2 million to settle a civil suit.

In the film, the night before the raid, Hampton accepts a drink from O’Neal, who had drugged it so Hampton would be incapacitated by the time police arrive. The raid survivors claim Hampton reacted so sluggishly he must have been drugged, but O’Neal denied spiking the drink.

In the final scene, Mitchell rewards O’Neal for his help by giving him a cash bonus and setting him up with a gas station (in reality, O’Neal got only the cash). He is racked with guilt for his role in the death of his friend, but he continues to work for the feds. The film ends with narration on what happened to the surviving real-life characters. The PBS documentary Eyes on the Prize II interviewed O’Neal about his life in the 1960s, and we see a clip of him trying to defend his actions. He delivers a rambling answer about how he supported the struggle. The film’s narration says O’Neal committed suicide the day the documentary premiered in 1990. The ending credits also show Fred Hampton’s son, Fred Hampton Jr., and celebrate his work carrying on his father’s legacy. Left unmentioned: In 1993, the younger Hampton was sentenced to 18 years in prison for firebombing two Korean stores.

Hoover did his best to defeat Hampton, but the Black Panthers ultimately won. Congress is considering removing Hoover’s name from the FBI’s headquarters while the Black Panthers enjoy official widespread approval. Today, Black Lives Matter claims to continue the Black Panthers’ mission. The FBI used to crack down on black radicals — now some of its agents publicly kneel before them.

Large group of FBI agents (25) take a knee with protestors near the national archive. pic.twitter.com/Trl9ARY9cs

— Jim Manico (@manicode) June 4, 2020

Judas and the Black Messiah is perfect propaganda for today’s “BLMania.” It glorifies black radicals and whitewashes their crimes. The closing credits don’t mention how many of America’s notorious gangs, such as the Crips, trace their origins to the Panthers. It doesn’t name the police officers the Panthers murdered or the innocent civilians they terrorized. Fred Hampton stands as a role model who does nothing wrong. Ignorant viewers who know little about the Panthers’ history may even see him as worthy of veneration.

- Post TagsCivil Rights Movement, Movie Review