The Great Replacement is the reduction of whites to a minority in what were once their neighborhoods, cities, states, or countries. It’s happening around the world, but many journalists think we shouldn’t talk about it. Here are editorials from the Washington Post (“The racist theory that underlies terrorism in New Zealand and the Trump presidency“) and the New York Times (“The White Extinction Theory is Bonkers“).

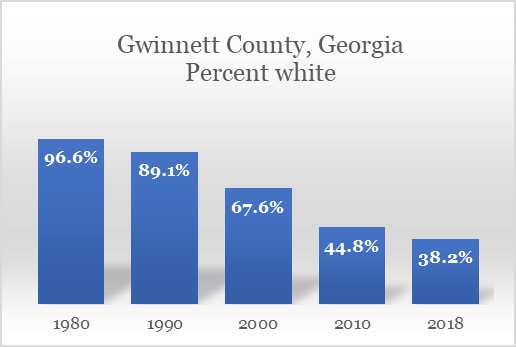

Yet in a column about the close Georgia governor’s race between Republican Brian Kemp and Democrat Stacey Abrams, Michelle Goldberg bragged in the Times that “We Can Replace Them.” Her theory was that demographic change would ensure Democrat victory. In the long term, she’s right. Gwinnett and Clayton counties are part of metropolitan Atlanta, and clearly show what demographic change means. They have not changed at the same pace, but the trends are identical.

Less than a month ago, in Gwinnett County, a ballot initiative to raise taxes to pay for an expansion of the MARTA light-rail/bus system was defeated with strong opposition from white voters. Whites are only 38 percent of the county, but 62 percent of them — especially older whites — don’t want MARTA in the county. In 1980, they were 97 percent of the county, and in 1971, they crushed an effort to bring in mass transit. Whites don’t like public transit because, as one put it this year, it means “mostly criminals coming out and taking what they want.”

Kevin M. Kruse’s book White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism describes the 1971 defeat:

Cobb County commissioner Emmett Burton endeared himself to many of his constituents when he promised to stock the Chattahoochee (river) with piranha if that were necessary to keep MARTA away. In a similar vein, two other counties Clayton County to the south and Gwinnett to the northeast, likewise rejected MARTA by massive 4-1 margins in 1971. As result, MARTA became a ‘metropolitan’ system in name only. The suburbs refused to take part, and thereby remained isolated from the poor and minority residents of the city for decades to come.

Gwinnett has changed. It went from 97 percent white in 1980 to 38 percent white by 2018. It was once reliably Republican, backing Ronald Reagan and George Bush in 1980, 1984, and 1988. It supported George W. Bush in 2004 with 65 percent of the vote, when the county was still roughly 48 percent white. In 2016, it turned blue and only 45 percent of voters backed Donald Trump.

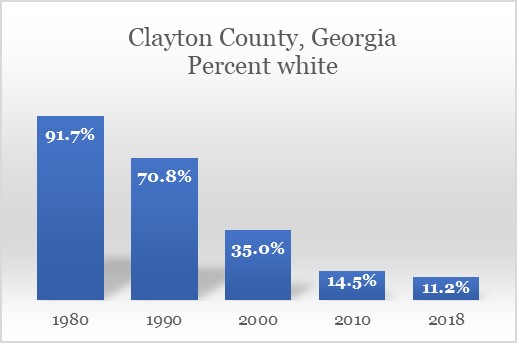

Clayton County saw an even quicker change. Its 1971 rejection of MARTA was reversed in 2014, when 74 percent of the county voted to extend service into the county. That was the first expansion of MARTA outside the downtown Fulton and DeKalb counties.

MARTA won after blacks had become 80 percent of Clayton County. In 1990, Clayton was 91.7 percent white. By 2000, it was 35 percent white, and by 2018, it was only 11.2 percent white.

Naturally, there were other political consequences: In 1996, when the county was barely majority white, Bob Dole got only 37 percent of the vote, and independent Ross Perot got 6 percent. In 2004, George W. Bush won 29 percent of the vote when the county was roughly 33 percent white. In 2016, Donald Trump got only 13 percent of Clayton County.

Clayton was the setting of Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone with the Wind, but in 2005, it elected a black sheriff. Victor Hill immediately fired 27 employees, including the top ranking white officers. Snipers were stationed on the roof to ensure an orderly departure. The 2014 MARTA victory was just another step in this transition from a white to a black county.

A 2006 ridership survey showed 76 percent of MARTA riders are black. (Some say the acronym stands for “Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta.”) However, many whites use MARTA to get to sporting events, and they keep their distance from blacks during these forays.

Just last year, a white man wrote this in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution:

I watch as the African-American passengers entering the train look for seats next to other African-Americans, and I watch white passengers seek out other white seat mates. I see the uncomfortable looks of white people who think the black kid dressed like a gang member is going to sit next them, and then the sigh of relief as he passes by. Mostly, it is then that I notice differences between the people who joined me at my embarkation and the people who have joined in the city. It’s not uncommon for me to watch an impromptu hip hop performance as the train treks south, a performance replete with phrases about violence, sex and race.

“I absolutely feel like an outsider,” says Mr. Bennett. “There is nothing I can say. There is nothing I can do.” No wonder whites don’t want MARTA coming their way.

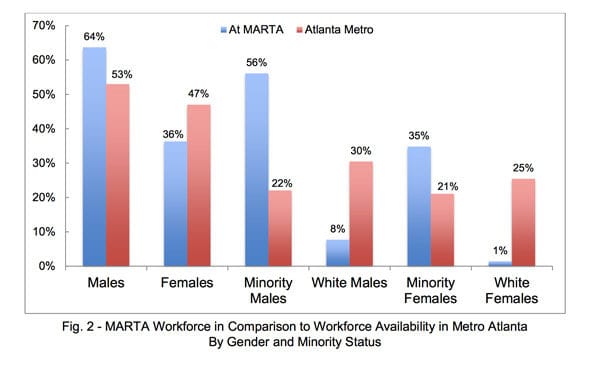

MARTA is also a jobs program for blacks. Last year, it reported that 83.7 percent of its 4,492 employees were black and only 9.1 percent were white. Whites declined from 9.6 percent in 2013.

Source: MARTA Equal Employment Opportunity Plan, 2018

The Great Replacement is happening, and shifts in Clayton and Gwinnett counties are examples. Population shifts change everything else. Journalists may pretend to like the change, but they can’t ask us to think it isn’t happening.